The word terrorism has been used to describe the activities of various groups over the last half century. For example, the British denounced the operations carried out by the Irish Republican Army as terrorism, while the same description was applied to the activities of such militant groups as ETA, the organization seeking autonomy for the Basque region lying between Spain and France, the Red Brigades in Italy, the Baader-Meinhof in Germany and similar movements in Japan and Latin America. However, when the word terrorism is mentioned today, what immediately springs to mind [in other than Arab and Muslim societies] is that an Arab or Muslim has committed an act of violence. The linkage between terrorism and Muslims has grown over the last six years, giving rise to the irrational fear of Islam known as Islamophobia. Still, there is no doubt that Muslims or Arabs are usually implicated in acts that are today described by the world as terrorism. There are two main schools of thought when it comes to addressing this phenomenon: one condemns Muslims in absolute terms, the other [Islamic] school justifies it as a reaction to what Muslims were and continue to be exposed to. With apologies to both schools, I would like here to adopt a novel approach by attempting to identify the sources or pillars of a phenomenon that has become one of the main areas of concern for a growing number of scholars and analysts throughout the world. Although I admit that the Arab/Muslim model of terrorism differs from others in terms of magnitude, in the sense that it is far more widespread than any other phenomenon described as terrorism [such as the Irish model], I believe that the difference is primarily due to the greater number of followers it can lay claim to. In other words, while the advocates of this form of terrorism are few in number and comparable to those operating in other cultural and religious contexts, the number of disciples attracted to the ideas propounded by the advocates of violence in the Islamic case is considerably larger. I believe those who deal politically or from a security angle with what is described as Islamic terrorism, as well as the analysts who study the phenomenon, disregard the extremely important distinction between 'advocates' and 'followers'. To my mind, the distinction is the key to finding solutions and dealing successfully with a phenomenon seen by many outside Muslim communities as the greatest challenge to humankind and civilization in the twenty-first century. Advocates who try to win over adherents to their cause by getting their message across through books, articles, lectures, speeches or sermons, cannot attract large numbers of followers unless the mental and psychological state of their audience and the political, economic and social conditions in which their prospective followers live make them receptive to their message, be it positive or negative. In all religions, sects and ethnicities there are advocates who disseminate extremely radical, sometimes extremely aggressive, ideas. But the number of followers who adopt those ideas differs from one case to another. For example, some Jewish and Christian leaders advocate ideas that are totally at odds with common humanity, with tolerance and acceptance of the Other – indeed, sometimes calling for death to others. But the number of followers who espouse their cause is nowhere near as great as those which advocates of some extremist Islamic ideas succeed in winning over. Many political regimes (unfortunately supported by some members of the intelligentsia) lump the members of both groups – advocates and followers – together and deal with them through the state's security apparatus, an approach that only compounds the problem. For although the advocates of violence are dangerous, I believe the security risk they represent is limited. Their message cannot in and of itself push any society to the point reached by a number of Muslim societies today. I also believe that using police methods against them will not produce positive results. Indeed, it could be counterproductive. Take the case of Sayed Qutb, the Islamic thinker executed in 1966. His ideas survived his death to become, after their merger with the Wahhabi doctrine, the primary ideological source on which most of the radical movements of political Islam draw today. The only way to curtail the influence wielded by the advocates of violence is through a concerted cultural and ideological campaign by enlightened members of the intelligentsia. For ideas can only be fought with ideas, beliefs with beliefs. And, if the campaign is to succeed it will not be thanks to the 'official' intellectuals who lack any credibility and who are more bureaucrats than independent thinkers. In the final analysis, however, it is not the advocates of violence but their followers who constitute the cornerstone of the phenomenon known as Islamic terrorism. The solution to the problem of political violence justified in the name of Islam lies in the answer to the following question: what is it that draws people, particularly young people, in many Muslim societies into the web of advocates who teach radical ideas, justify violence and call on them to isolate themselves from the course of human civilization? I believe all the reasons behind the appeal the advocates of violence hold for the young in Muslim societies can be summed up in one word: anger. The sources of this anger are many, and I believe we should try to understand, not condemn, it. And, if understanding leads to compassion, there is nothing wrong with that. From a humanistic and historical perspective, to understand and sympathize is not to condone, justify or accept. Rather, it is to recognize that we are dealing with patients suffering from a debilitating and dangerous disease, patients who need treatment, not security procedures, violence, coercion and torture.

Let us now identify the main – but not the only – sources of anger among young people in many Muslim societies:

1- The well-founded fear that their prospects of making a decent living are extremely limited, with young people, both educated and uneducated, unable to find suitable employment that can provide them with a reasonable standard of living.

2- The enormous gap between the haves and have-nots; not so much the fact that there is a gap as its sheer magnitude.

3- The ambiguity surrounding how the wealthy acquire their fortunes, the powerful their power and the famous their fame. This was not always the case. For example, people knew that Mohamed Talaat Harb was a rich man, but they never thought he had amassed his wealth by dubious means.

4- The disappearance of fairness from most fields of employment and occasionally even from commercial activities, where cronyism counts for more than merit and where those who enjoy the backing of political muscle [which is not available to the vast majority] are assured of success and advancement.

5- The absence of personalities with leadership qualities in most areas.

6- The close relationship that exists between the plutocrats, the executive branch of government and the media.

7- Rumours about corruption in high places that, despite the absence of concrete evidence, people tend to believe.

Conclusion:

A study of these seven pillars on which the anger which spawns violence, rejection, hostility and terrorism rests is a political, cultural and strategic matter. To address it exclusively from a security perspective does a grave injustice to society and to all the parties concerned, including the security institutions themselves. For at the end of the day, police methods are no match for phenomena with numerous political, economic, social and cultural dimensions.

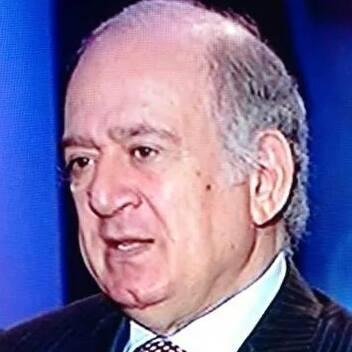

The Seven Pillars of Terrorism

By: Tarek Heggy - on: Wednesday 15 November 2017 - Genre: Politics

Upcoming Events

Arabia Felix - Alarabia Alsaida in Bayt Yakan

April 15, 2025

Arabia Felix by Thorkild Hansen, and translated by...

A writer, a vision, a journey: a conversation with Professor Ilan Pappe

March 15, 2025

This event took place on 15 March, 2025 . You may...

مسافر يبحث عن ماء

February 17, 2025

تقيم نقابة اتحاد كتاب مصرشعبة أدب الرحلات تحت رعاي...

Online discussion of The Vegetarian by Han Kang Nobel Prize winner 2024

November 08, 2024

This discussion of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian...