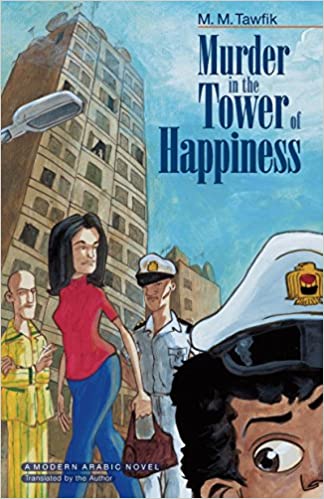

Murder in the Tower of Happiness

M. M. Tawfik

Cairo-New York: The American University in Cairo Press, December 2008

Pp. 340

Reviewed by Sally Bland

Jordan Times - 31 August 2009

In this novel, Egyptian writer M. M. Tawfiq infuses a murder mystery with philosophical overtones, as well as biting social critique of everything from corruption to the effects of globalisation. Most of all, the story highlights the differences in life style and outlook between Cairo’s three main classes: the super rich, the educated middle class and poor workers.

“Murder in the Tower of Happiness” has several things in common with Alaa Aswany’s “The Yacoubian Building” (This is not to imply that either author copied the other; the Arabic editions of the two books were published within a year of each other, precluding such a possibility). In both novels, a multi-storey building serves as a literary device unifying a series of characters and events, but while the Yacoubian Building is a real place, the Tower of Happiness seems to be a symbol for any one of the luxury high rises overlooking the Nile. Both novels contain piercing critique of modern day Egypt, but while Aswany sticks to realism, Tawfiq plunges into surreal dimensions: The spirit of the murder victim reappears as a narrator and main player, as the plot rushes to its conclusion on the eve of the second millennium.

A few months after the beautiful actress, Ahlam (Arabic for dreams), is found dead in the Tower of Happiness, various pieces of furniture - most notably a piano - are seen flying from the 13th floor where she is presumed to have been murdered. This sets off a chain of events that involve Sergeant Ashmouni, the traffic policeman stationed on the street below; Abd Al Malak, an unemployed MIT graduate who is hired by a rich resident of the tower to rid it of ghosts; and journalist Islah Mohandes. The story is told in alternating chapters from these three characters’ points of view. At first, it is third person narrative, but then it switches to first person as the author steers the plot beyond external events and into interiors to reveal the characters’ feelings, aspirations, soul-searching and, most of all, their disillusionment, despair, and the end of their dreams of dignity and happiness.

The two men don’t really want to get involved in the case of Ahlam’s murder, but events push them in that direction. They are mostly seeking peace of mind and personal happiness with a woman of their choice, but ironically, happiness is the hardest thing to find once they get involved with the tower of this name. Against their will, they learn quite a lot about corruption and depravity, how the rich and powerful can literally get away with murder, and how they, the powerless, can hardly avoid being bought off. It is not just the temptation of money; those who don’t cooperate may pay with their lives.

In contrast, the third narrator, Islah, seeks truth and justice for Ahlam, and is willing to take risks, but she also finds it difficult to avoid being silenced.

While Ahlam’s name and the Tower of Happiness appear as metaphors for the type of life and country aspired to by ordinary Egyptians, her murder signifies what went wrong. Though the super rich live only for the moment, ordinary people are embedded in and haunted by their history, still discussing the import of the ‘67 and ‘73 wars, Nasserism, Islamism, Sadat’s intentions in visiting Jerusalem, the implications of peace with Israel, relations with the United States, etc.

While the irony of the novel’s title sets the tone, Tawfiq’s writing style captures the reader’s imagination from the first page. His images are strikingly graphic and original, sometimes shocking, and perfectly suited to exposing contrasts, whether in the city, the excesses of the tower’s inhabitants, or the characters’ secret dreams and fears. As Islah comments on the view of Cairo from an upper floor of the Tower of Happiness: “This city has nothing to do with the one I live in, stacked with garbage in every corner, reverberating with human voices, corroded by the dust and pollution that mix with every atom of its air. In fact, the city I live in is the exact opposite of the beautiful picture behind the young millionaire, the one they’ve skillfully erected to erase poverty, depravation, lost dreams and the wasted years of youth, a perfect picture that shows no trace of the volcano brewing in the depths of each of us.” (p. 252)

Tawfiq has achieved a seamless blend of the personal and political, whether in terms of dreams or disillusionment.