During the intense period of witch-hunting in Europe, numerous women faced trials and executions. One such woman was Katharina Kepler, the mother of the renowned astronomer Johannes Kepler. In August 1620, she was apprehended from her daughter's residence and detained on 49 charges of witchcraft. She was ultimately acquitted, with Johannes credited for providing a strong defence rooted in scientific understanding. However, uncertainties persist: Was her exoneration truly based on scientific evidence? And did Katharina undergo the same trial process as others accused of similar charges at the time, leading to a fair acquittal?

The Compassionate Defence of Katharina Kepler

When examining Katharina Kepler's biography, it becomes apparent that her son utilized his scientific expertise to assist her during her trial. However, upon closer examination, there is limited direct evidence or documentation explicitly demonstrating how he did so.

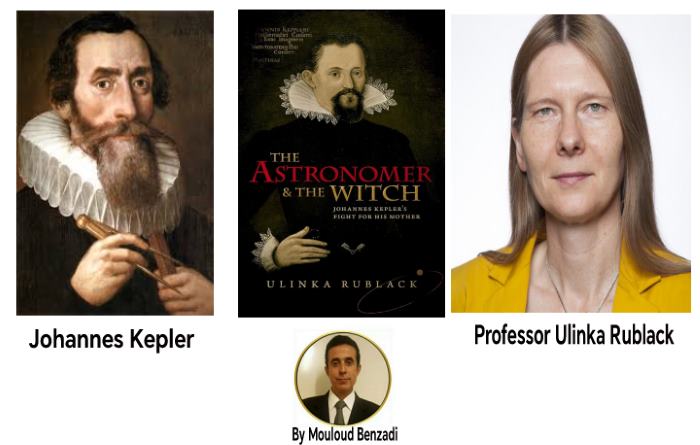

In his mother's defence, Kepler appears to present compassionate arguments instead of scientific evidence. In the book "The Astronomer and The Witch," Cambridge Professor Ulinka Rublack wrote, "Right from the beginning of the case, Kepler thought of her physicality as a primary cause of people's fear and rejection, portraying a conflict between the young and the old. He would have been influenced by classical literature that depicted women's physical decline as grotesque, and likely encountered many older women who took care to maintain their appearances." Another passage from the same book states, "Kepler focused on her aging body as repulsive, 'ungestalt', and almost inhuman in his writing on her behalf. The guards even lent the toothless woman a broken pocket-knife to cut meat into small pieces for her to swallow without chewing." These passages highlight a compassionate understanding of the human experience, aiming to provoke empathy and insight. They do not conform to the typical structure of a logical argument based on evidence, reasoning, and factual analysis commonly found in a court of law.

Moreover, Kepler employs speculative arguments based on conjecture rather than direct evidence or legal precedent. This is demonstrated by the following statement from Rublack's book, "In Reinbold's case, there was some evidence indicating that she had consumed strong medicines that could have been harmful. Kepler proposed the idea that she might have mistakenly used the wrong jug when visiting Katharina, who had always consumed her own blend of healing herbs without any adverse effects." This statement relies on supposition, introducing a theory or scenario without direct evidence to substantiate it.

Kepler’s Disingenuous And Manipulative Actions In Court

Kepler's attempt to depict his illiterate mother as a reliable healer, despite uncertainties about the preparation of the drinks she administered to patients, could be viewed as an exaggeration and a deliberate strategy to manipulate perceptions and obscure the truth. Ulinka Rublack astutely pointed out, "His strategy, in essence, was to present his mother in a different light—not as an old, marginalized, illiterate, and superstitious woman, but as a devout citizen who effectively passed on and enhanced medical knowledge, conscientiously utilizing herbs for her own well-being."

In contrast to his argument, his mother confessed in court that the drinks she prepared were often left in their jugs overnight or for several days, compromising their quality. This clearly strengthens the argument that her methods might not have aligned with accepted standards of care or knowledge concerning the preparation and preservation of remedies.

Furthermore, Kepler resorted to derogatory language and personal attacks when rebutting witnesses, as observed by Ulinka Rublack. She notes, "Losing his composure in civil discourse, Kepler referred to one of them as 'a fable-woman,' and Beittelspacher as 'a fable-man,' 'idiot,' and 'little girl's schoolmaster,' implying a lack of intellectual depth."

The use of such language and pejorative terms by Kepler is unbecoming of someone in his position and could potentially tarnish his reputation as well as raise questions about his professional conduct in handling the case.

Fairness Doubts in Katharina’s Trial

One crucial question arises regarding the fairness of Katharina’s trial and subsequent acquittal. In the context of witch trials during that period, the use of torture was a commonly employed method to extract confessions from the accused. The absence of such a rigorous test, in the form of actual torture, for Katharina, could be seen as a deviation from the standard procedures of the time. Furthermore, the mention that many accused witches only confessed after being subjected to torture underscores the significance of this omission in Katharina’s trial.

The disparity in treatment in the trial in favour of Katharina was also highlighted in "The Astronomer and the Witch," where it says, "It is more than likely, though, that Kepler knew from his Tübingen friends that what would now follow was a pretence, and that he would have let Katharina know. He could prepare his mother for encountering a third-rate occasional executioner—the psychological pressure would therefore be low. In Nuremberg, prisoners during the same period would be tightly bound on the rack or a chair to see the legendary executioner Franz Schmidt describe his instruments of torture in the most terrifying manner, boasting of how he had used them to extract the truth from the most obstinate villains. Yet Katharina probably knew that she would not suffer any further pain if only she kept on denying her guilt." This statement suggests that Katharina would likely have been informed that her trial was a pretence, relieving psychological pressure. This insinuates an unfairness in the treatment of Katharina, as she would not be subjected to the same psychological and physical pressures experienced by prisoners facing similar charges in Nuremberg.

The Suspicious Portrait of Katharina Kepler

Despite her acquittal of witchcraft in 1621, some historians describe Katharina Kepler in a highly negative manner. In Arthur Koestler’s renowned history of astronomy, “The Sleepwalkers,” Katharina is referred to as a “hideous little woman” with an evil tongue and a “suspect background.” Furthermore, John Banville’s award-winning historical novel, “Kepler,” paints a vivid picture of Katharina as a crude old woman who engages in dangerous practices such as boiling potions in a black pot and meeting with hags in a cat-infested kitchen. This portrayal depicts her as a scary, disgusting figure and even suggests she may be a witch. Additionally, Katharina herself aroused suspicion and raised questions through her strange behaviours. Although illiterate, she chose to make and administer herbal remedies to patients, which made them sick. As mentioned in The Astronomer And The Witch “Katharina explained that some of the drinks she prepared had remained in their jugs overnight or for some days, so that their surface might have developed some skin which might have implied that their properties had changed.” She also added to her mysterious and unsettling reputation by asking a gravedigger to dig out her father’s skull to use it as a drinking cup, one of the charges raised against her during the trial. She even admitted to telling a man that she would make bad weather. These strange actions undoubtedly give rise to suspicions and justify questions regarding her intentions and involvement.

Katharina’s Fate beyond Kepler’s Defence

While Johannes Kepler's presence and attempts to defend his mother in court undoubtedly played a role in the proceedings, it is worth noting that his scientific renown and status in the 17th Century Scientific Revolution may have led to an overemphasis on his contributions to the case. Despite his efforts, Kepler’s submissions were ultimately rejected by the judges, as described in "The Astronomer And The Witch": “Katharina and Johannes Kepler appeared together in court, and Kepler demanded at once to be able to skim through the final accusation. This came as a shock. Tightly argued and referencing Latin legal as well as theological commentators, Gabelkhover left no doubt that Katharina had to be tortured. She was held responsible for several acts of harm against people and animals, as well as for attempting to bribe the Leonberg governor in order to avoid any hearings before she escaped the country. Kepler’s defence was refuted for diluting clear evidence, for instance, that she had promised Einhorn the silver cup. She had been a suspect person present at places where harm had happened. Moreover, she had practiced soothsaying, had a bad reputation, and a son who said that she had driven his father away. Her testimony was inconsistent.”

Further investigation is necessary to substantiate claims that Katharina was released thanks to her son's scientific evidence. Uncertainties persist regarding the fairness of the trial as Katharina was not subjected to torture, which was widely practiced to force others to confess. There remain questions about her unusual actions, such as her request to unearth her deceased father's skull and her involvement in crafting and administering medications to patients, causing them to become sick. Additionally, the trial raises questions about Johannes Kepler's part in securing his mother’s release: What scientific evidence did he present to the court? What evidence supports the claim that “Kepler’s scientific evidence” was behind Katharina’s acquittal when reliable records relating to the case state that Katharina’s testimony was found to be inconsistent, and Kepler’s arguments and submissions before the court were not persuasive enough to counter the accusations brought against her by several individuals. Katharina was subsequently released due to a lack of evidence and for compassionate reasons, particularly considering her age, as mentioned by Ulinka Rublack in her book, “Much of the evidence was not sufficiently supported and, given her old age, did not justify proper torture.”