Nigel Ryan Ahram Weekly- February 2002

There had been no sculptor in my country for seventeen hundred years and the images that appeared among the ruins and sands at the edge of the desert were considered accursed, evil -- no one should go near: so said Mahmoud Mukhtar, or so he is quoted as saying, in Moukhtar ou le réveil de l'Egypte, Badr El-Din Abu Ghazi and Gabriel Boctor's study of the sculptor. The volume appeared in 1949, 15 years after Mukhtar's death at the age of 41, and so one might have grounds to be a little suspicious of direct quotations. But if Mukhtar really was keen to present himself as the first Egyptian sculptor for two millennia, then that is an understandable vanity, and on a great many levels it is likely to be true.

The stories that would eventually circulate around the young Mukhtar are equally understandable: "He was a precocious child who displayed an early talent for modelling forms out of mud imbued with Nile water or clay dried in the hot sun and baked in bread ovens. The forms he created enacted ancient folk tales. They were named after heroes like Antar and Diaz, and Abu Zayd El-Hilali, whose epics were sung by the village story tellers."

This time the quotation is from Liliane Karnouk's Modern Egyptian Art, which carries, as its rather more programmatic sub-title The Emergence of a National Style. We have long liked our artists to be precocious, there is nothing new in that, and the sub-title is perhaps sufficient to explain the invocation of earth, folk epics and, the Nile.

The outline of the plot is well-known: the village boy happened to be in Cairo when he heard about the School of Fine Arts, newly founded by Prince Youssef Kamal. So desperate was his urge to learn more of sculpture that he wandered through the gates of this new institution and spoke to the first person he saw, who happened to be M. Laplagne, the director of the school and its professor of sculpture. Mukhtar was 17. He joined the school, was in time granted a scholarship to Paris, to the Ecole des Beaux Arts, and the rest, so to speak, is history.

Do not underestimate the burden of being the first Egyptian sculptor in two thousand years: it is almost certainly more than any single man should be expected to bear. It is a strain, too, given the manner in which Egyptian art history is so mercilessly reified, to be among the first graduates of the School of Fine Arts, which opened in 1908 and was financed for two decades by Youssef Kamal. Yet given the chronology, given the context, there is an inevitability about Mukhtar being awarded the dubious honour of being proclaimed a national treasure. Yet nothing has so obscured the real significance of a generation of Egyptian artists than being pronounced pioneers.

Mukhtar has been accorded all the trappings of that status. For many years the museum devoted to his work stood proudly on a site opposite the Opera House, though since the late 1990s it has been closed, for renovation and remodelling, so the sign outside announces, though quite why this is taking so long is anyone's guess. Still, the museum is there, and for the past month Mukhtar has been the subject of a small retrospective, in that most glittering of public exhibition spaces, Horizon I, attached to the Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil Museum.

And this is something of an event, if only because, since the closing of the museum the closest anyone has been able to get to Mukhtar's work is to view the large public commissions through a fog of exhaust fumes -- the statue of Saad Zaghloul, standing at the end of Qasr El- Nil Bridge, hand raised atop his lotus columned pedestal, and the peculiarly unattractive Egypt Awakening, a neo-Pharaonic farrago that has sat in front of the avenue leading to Cairo University for as long as most people can remember. Yet these large public commissions have become all but invisible beneath their iconic accretions. They have become fixtures of the urban landscape, vague points of reference, and it might register that something is not quite right, should they be removed but when, in all honesty, did you last really look at them? Their meanings were, in any case, fixed half a century ago, and as is always the case with official histories, the meaning is non-negotiable, regardless of whether or not it accommodates the facts. And in the case of Egypt Awakening -- which, despite the heavy-handedness of the symbolism (perhaps because of it) lends itself to any number of readings -- this constitutes a serious problem.

The Horizon One show includes few public commissions, though the maquette for the Saad Zaghlul statue is included. Instead the gallery is full of small scale pieces, and a remarkably eclectic lot they are. There are large numbers of limestone sculptures, of fellaha going about their endless tasks. These date mostly from the late twenties: they fill water jars on the banks of the Nile, carry baskets on their heads, or water pots, or trays of cheese. They are schematised to the point where the strains of the physical tasks they undertake disappears beneath the straining after symbolic weight, for this is no peasant women, but rather Egypt, or its essence. And essences are notoriously difficult to capture, particularly in limestone. They are as convincing as Britannia, or Marianne, or Mother Armenia: old-fashioned, they increasingly become palatable only when viewed as a kind of irredeemable kitsch. Formally, when they make use of ancient Egyptian models, it is in a manner mediated by the bluntly obvious strategies of Art Deco, which from the viewpoint of the 21st century might make of them an interesting footnote in the promulgation of that increasingly unattractive style, but on such footnotes lasting reputations rarely rest. Far more interesting and, I suspect earlier, though it is not dated, is a portrait bust, The Head of Mrs H.A. Here, the impulse to stylise, to elongate, operates in direction of the particular: the result is a perfectly realised flapper, the shoulders on which the head rests having been turned into a piece of machinery, a kind of piston. It is a piece that, though patently a portrait of an individual, speaks eloquently of her time

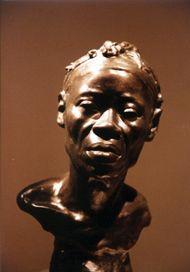

Head of a Black Girl, a bronze dating from 1910, exhibits a similar intent to portray, though this time the modelling is less fashionable in its reductionism. the result, though, is one of the most powerful bronze sculptures in the current show: tellingly, it carries far more weight than the more celebrated caricatures of Egyptian types. For all his positioning within the Egyptian nationalist canon Mukhtar was a product of a conventional French training. It is apparent in occasional conversation pieces, such as Spirit of the Fields, a jolly, bearded faun across whose knees sports an equally jolly nymph. It is apparent, too, in the Head of the Nile Bride, a bronze from 1929, which despite the Egyptian trappings is a vision of Egypt viewed through the prism of a fashionable Parisian salon. There is an interesting letter, again quoted by Abu Ghazi, which Mukhtar sent to the functionary, from the Department of Public Works, who had to register him as a public servant in order for Mukhtar to receive the agreed allowance during the time he was working on Egypt Awakening. "In letters dated January 5 and 12," wrote Mukhtar, "I am asked to provide two letters of good conduct. well, it happens that my conduct is bad. I have a bad temper. I was sentenced to 15 days in prison. Furthermore, I wear a beard and that is frowned on here. I am a bachelor, and I frequent certain particular houses. You see, I am therefore condemned to never become a public servant, ever. Please accept the expression of my distinguished regards." It is the letter of a graduate of the Ecole des Beaux Arts, and one who, whatever else he was about, was not going to abandon the Parisian art student's favourite hobby of shocking the bourgeois. A salutary thought: how would the reputations of Mukhtar's contemporaries have fared had their sculptures been forced to carry the burden of national struggle. I think here of those second ranking artists, men like Gaudier-Brezska, Boccioni, or even Epstein. Epstein, of course, lived to dismantle the Rock Drill, and to redraw his earlier reputation. Brezska had the good fortune to have Ezra Pound as a subject, rather than some essential spirit of his native land. And Boccioni, whose Unique Forms of Continuity in space is humanised in Mukhtar's rather more attractive Khamsin, had his talents coopted by the Italian avant-garde, and not the Wafd.