Robin McKie

science editor The Observer October 3, 2004

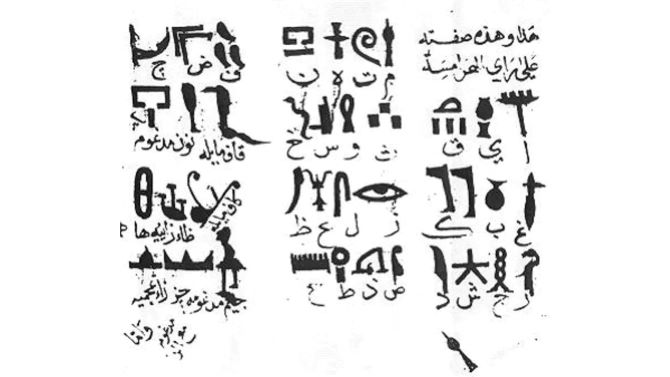

It is famed as a critical moment in code-breaking history. Using a piece of basalt carved with runes and words, scholars broke the secret of hieroglyphs, the written 'language' of the ancient Egyptians. A baffling, opaque language had been made comprehensible, and the secrets of one of the world's greatest civilisations revealed - thanks to the Rosetta Stone and the analytic prowess of 18th and 19th century European scholars. But now the supremacy of Western thinking has been challenged by a London researcher who claims that hieroglyphs had been decoded hundreds of years earlier - by an Arabic alchemist, Abu Bakr Ahmad Ibn Wahshiyah. 'It has taken years of painstaking research to prove this,' said Dr Okasha El Daly, at UCL's Institute of Archaeology. 'I was convinced that Western scholars were not the first, and I have found evidence that shows Arabian scholars broke the code a thousand years ago.' The Rosetta Stone was found embedded in a fort wall by French engineers during Napoleon's campaign in Egypt. The stone - now displayed in the British Museum - contains a text in Greek, Coptic and hieroglyph, but still required another 23 years' work to be decoded, a task achieved by Jean-Fran�ois Champollion, a student of ancient languages. Champollion's breakthrough came in 1822 when he realised hieroglyphs should be read, not as symbols of ideas or objects, but as a phonetic script. The sound associated with each symbol was crucial to deciphering it. It was a 'eureka' moment. 'Je tiens mons affaire (I've done it),' Champollion shouted, before falling into a dead faint for five days. He awoke to continue his work, but died 10 years later of exhaustion and is buried in Paris's P�re Lachaise cemetery. Pieces of papyrus are still placed on his grave in recognition of his great work. But now it is claimed that Champollion had been beaten by Arabian scholars who, eight centuries earlier, had twigged that sounds were crucial to their decoding. 'For two and half centuries, the study of ancient Egypt has been dominated by a Euro-centric view that virtually ignored Arabic scholarship,' said El Daly. 'I felt that was quite unjustified.' An expert in both ancient Egypt and ancient Arabic scripts, El Daly spent seven years chasing down Arabic manuscripts in private collections around the world in a bid to find evidence that Arab scholars had unlocked the secrets of the hieroglyph. He eventually found it in the work of the ninth-century alchemist, Ibn Wahshiyah. 'I compared his studies with those of modern scholars and realised that he understood completely what hieroglyphs were saying.' El Daly stressed that Muslim scholars had not simply been handed the secrets of hieroglyphs after Egypt was taken over by Islam. 'The secret of the hieroglyph was lost and then rediscovered by Arab scholars, who used diligent work to break their code, eight centuries before Champollion,' he said. 'These were people who possessed great astronomical and mathematical knowledge. Decoding hieroglyphs was just the kind of thing they would have been good at.'