Naguib Mahfouz (1911-2006)

Mahfouz was born in an old quarter of Cairo (Gamaliya) in 1911 and lived there until the age of 12, when his parents moved to a newer suburb; however, he achieved fame as the chronicler of the old neighborhoods of Cairo, and has credited the Cairene world as his inspiration. He was the youngest of seven children, but at 10 years younger than his next-older brother really had no sibling relationship; instead, he emphasized friendships outside of the house. Politics and religion were evidently important topics of conversation in his home, although Mahfouz has remained relatively silent about his family.

Mahfouz began his education at the kuttab (Qur’an school), where the emphasis was on Islamic religion and basic literacy, then went on to primary school. When he was 7, Egypt was caught up in a revolution against British rule, the memory of which continues to dominate his political awareness; images of the revolution recur in many of his novels. He read historical and adventure novels, specifically citing Sir Walter Scott and H. Rider Haggard, but also read widely in both classical and contemporary Arabic literature. (In various statements after he achieved fame as a writer, he specifically mentioned a wide variety of Western writers, most notably Tolstoy, Proust, and Mann.) He then attended King Fu’ad I University, graduating with a degree in philosophy in 1934. As he matured, he gravitated toward a socialist worldview and became increasingly critical of “Islamist” politics.

He began to study toward an M.A. while occupying various bureaucratic positions from 1934 until 1971, when he became affiliated with the daily newspaper Al-Ahram. In his entire life, he was out of Egypt only twice; he even turned down the opportunity to travel to Stockholm to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1988. Prior to this award, few in the West knew of him; at that point, he had written 38 novels or novellas and 12 collections of short stories and plays, and had received several awards in the Arabic world. His added prominence came with a price, however, as strict Islamic fundamentalists have suggested that a fatwa should have been declared on him after he wrote Children of the Alley, as it would have prevented Salman Rushdie’s subsequent writing of The Satanic Verses. In October of 1994, he was attacked and stabbed on a Cairo street, evidently by a fundamentalist.

His early writings included translations from English and stories about ancient Egypt; but his most significant early novels trace changes in the lives of Cairo's petty bourgeoisie as a national consciousness emerged after the 1919 Revolution. He has been compared to Zola, Balzac, and Dickens, although most critics emphasize his independent Arabic nature. However, after receiving the Nobel Prize, Mahfouz himself said that his work upholds principles widely associated with European civilization - but he has also argued that these principles can be found in Islam as well.

Mahfouz was part of a generation of Egyptian writers who emerged during the 1940s and '50s calling for the reform of Egyptian society. During the 1940s, Egyptian society experienced a major shift as poor workers began moving into the cities seeking employment; under the stress of the changing society, some affiliated with the socialists or communists and others with the Muslim Brotherhood . There was also a great increase in the number of novels published, both because of the increasing respectability of the genre among Arab readers and the foundation of new publishing. Mahfouz, who took part in this explosion of the Egyptian novel, is “the most significant” contributor to the Arab novel in the 20th century, surpassing any rivals in terms of volume and variety of literary output, originality, and seriousness .

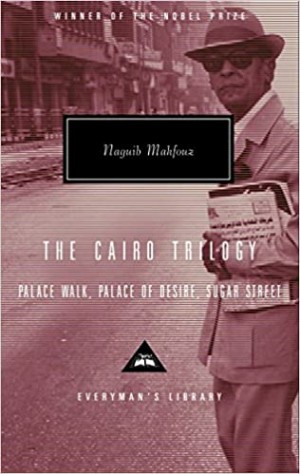

In his earlier, realistic novels, Mahfouz clearly seems to favor “secularist socialism,” aligned with modern science, over “revivalist (fundamentalist) Islamism,” as is shown by his presentation of characters espousing each perspective. According to Trevor Le Gassick, “Mahfouz saw his stories as a means to bring enlightenment and reform to his society.” Mahfouz's Cairo Trilogy (published 1957) in particular contributed to both radicalism and social realism in Egyptian literature, but all of his novels up to at least 1957 strive to give a realistic view of life in the old part of Cairo - many of these novels were named for streets or neighborhoods in the old city. Somekh argues that one important ingredient in Mahfouz's work is the complete identification with the plight of Egyptian masses - in other words, his sympathy is with the downtrodden. These are the novels that the Nobel Committee specifically cited in awarding the Prize.

He stopped writing for five years after the 1952 revolution (which also coincided with the completion of his Cairo Trilogy). In Children of the Alley (1959) , he introduces a warning recognition that science, too, may be misused, as the magician’s invention of a powerful explosive weapon is appropriated by the forces of tyranny, not those of liberation (Beginning with Children of the Alley and The Thief and the Dogs in 1962, Mahfouz seemed to move away from his realistic style to a more inner-directed narrative of character's thoughts. Novels of this period tend to be more focused on individuals than the earlier works, but Somekh (perhaps the most expert writer on Mahfouz in English) suggests these works are "neo-realistic" in that they avoid detailed description of setting and psychology but nonetheless present an accurate picture of realistic Egyptian society.

Mahfouz again wrote no novels for several years after Egypt’s defeat in the Six Days War . Following the hiatus in literary production following the 1967 Egyptian defeat, his work has been even more experimental, using a wide variety of forms

* * * * * * * * * * **

Mahfouz claims that all of his books are political in some way, and that his work revolves around the three poles of politics, faith and love - but politics "is by all odds the most essential". Mahfouz is highly sensitive to political events; e.g., he used the 1919 Egyptian revolution as the background for his Cairo Trilogy, and exhibited prolonged periods of creative stasis followed by new writing directions after both the 1952 revolution and the 1967 loss to Israel in the Six-Day War . His politics became a source of controversy in 1979 when his public support of Sadat's treaty with Israel brought denunciations from Islamic fundamentalists and a ban on his works in some Arab countries.

While his works are often realistic, characters and events often have a further significance, which Somekh says is not quite mystic symbolism but may approach it. For instance, the family is often both a family and a condensed version of Egypt as a whole.

Some of his works translated into English

Palace Walk (Book 1 of the Cairo Trilogy) (originally published in Arabic 1956)

Palace of Desire (Book 2 of the Cairo Trilogy) (originally published in Arabic 1957)

Sugar Street (Book 3 of the Cairo Trilogy) (originally published in Arabic 1957)

Children of Gebelawi (originally published in Arabic 1959)

The Beginning and the End (originally published in Arabic 1956)

Adrift on the Nile (originally published in Arabic 1966)

The Journey of Ibn Fattouma (originally published in Arabic 1983)

Midaq Alley (originally published in Arabic 1947)

The Harafish (originally published in Arabic 1977)

The Beggar (originally published in Arabic 1965)

The Thief and the Dogs (originally published in Arabic 1961)

Autumn Quail (originally published in Arabic 1962)

Wedding Song (originally published in Arabic 1981)

The Search (originally published in Arabic 1964)

Fountain and Tomb (originally published in Arabic 1975)

Miramar (originally published in Arabic 1967)

The Time and the Place and other stories

Respected Sir (originally published in Arabic 1975)

Arabian Nights and Days (originally published in Arabic 1982)