Khairy Shalaby (خيري شلبي) (January 31, 1938 – 9 September 2011) was an Egyptian novelist and writer. He wrote some 70 books, including twenty novels, critical studies, historical tales, plays and short story collections

Khairy Shalaby or Khairi Shalabi was born in Kafr al-Shaykh village, the Nile Delta, in 1938, he is one of Egypt’s most distinguished and popular authors.

Many of his books became bestsellers and were translated into several languages including English, French, Italian, Russian, Chinese, Urdu and Hebrew, and some adapted for film and television.

The Arabic edition of The Lodging House, Wikalat 'Atiya, was awarded the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature in 2003. The English edition (AUC Press), translated by fellow Egyptian Farouk Abdul Wahab, professor of Arabic literature at the University of Chicago, won the 2007 Saif Ghobash-Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation.

Among the comments on Shalaby’s work by the judges were “The Lodging House is a wise, anarchic, ribald, compassionate compendium of life at its most precarious and most ebullient” (Maya Jaggi), “The portrait that it offers is authentic, affectionate and critical” (Roger Allen), “an outspoken message, in defence of the forgotten, the downtrodden and the poorest of the poor” (Saadi Youssef)

Shalaby saw himself as writing the literature of "the Egyptian street "; and feels a duty to give new life to people from the cities and villages through his characters.

He was awarded the Egyptian National Prize for Literature 1980-1981, and was editor-in-chief of both Poetry Magazine and Library of Popular Studies books series published by the Egyptian Ministry of Culture.

The narrative eye

Profile by: Mohamed El-Assyouti

Source: al-ahram weekly

A rural environment sensitive to the flow of history provoked the seven-year-old, preoccupying him with big questions. His family had a history of its own: the photographs proved it. There was his great-grandfather, overseer of the Khedivial domains; there were his uncles, one an Azharite sheikh, another a village sheikh, many agricultural labourers on an ancestor's sprawling estate, which was later distributed among them, each receiving a fragment.

Khairi Shalabi, writer of novels and short stories, remembers the 1952 Revolution, and how it turned everything upside down. "Classes exchanged positions without integrating diverse social and cultural elements in class struggle, as had been the case before." He was surprised to see society subjected to the rule of "an emerging class, comprising a hybrid of social strata that sacrificed everything for their political careers, yet had no knowledge, culture or traditions." As a teenager, he pondered big questions, whether or not the answers were obtainable. (Recently, he stumbled upon the answer to one of the innumerable questions that had haunted him as a child; he expressed it in his book Baghlat Al-'Arsh or The Throne's Mule.) A perplexed outlook gradually developed from this flood of questions, the most enigmatic of which was his father.

Ahmed Ali Shalabi, Khairi Shalabi's father, was a political activist, one of the founders of the Wafd Party, and a former employee at the Alexandria Lighthouse Administration. He named his first son -- born after two unsuccessful marriages -- Khairi. At the subou' (ceremony to celebrate the newborn's first week of life), Hafiz Ibrahim, the Poet of the Nile, dedicated an improvised poem to the child, who died before turning 15.

Khairi Shalabi was named after his dead brother, as is the custom among families seeking to avert the evil eye from a new child; he also inherited much of his brother's radiance. At times, he even imagined that Ibrahim's poem was a prophesy of his own birth. This was one of the incentives spurring his young mind beyond the village that surrounded him.

Khairi Shalabi's dead sibling, in truth, had only been a half-brother. His father married a fourth time -- this time, a 12-year-old girl of Circassian origin. The union produced a veritable tribe of children. The old man's back bent under the burden of these new responsibilities, but he faced the challenge valiantly, like any youth starting a household. To little Khairi, he was an almost legendary being, an object of curiosity. "Where does he find his ability, power, valour and determination?" wondered the bewildered son. He had witnessed his family's tumble down the social ladder. Ahmed Shalabi had incurred the antagonism of many people because of his declared political positions and poetry -- fired, then hired again, demoted to a position beneath his qualifications, and finally driven out of government work. "Politics devoured him, financially and psychologically," says Shalabi. He had to rely on his own means to feed his vast family. Still, he wrote poetry and told jokes; his gift for story-telling was evident in his ability to compress details into a condensed, concise, ironic theme when relating events.

To Khairi Shalabi, only one thing was certain: "Ours was a family that had a past, but not a very bright present." Their gramophone -- "the teller of stories", or "the singing machine" -- and their collection of over 3,000 records -- was all that remained of past grandeur. These were enough, however, to inflame young Shalabi's artistic imagination. He developed a profound link with the music scene in Cairo, poring over the information on the record covers. Fortunately, the village's cultural activities complemented the fledgling writer's domestic background in stimulating his creativity.

The village's sole means of mass entertainment was the narration of Sira Sha'biya (popular epics) and stories from The Thousand and One Nights. There were also lectures on Tafsir (the exegesis of sacred texts), Sunna (the Prophet's practice) and Hadith (collections of the Prophet's sayings). Every night, the men of the village gathered in the mandaras (reception parlours) of the various houses to listen to the storytellers and scholars; the size of each gathering was proportionate to the grandeur of the family that hosted it.

"An average of 750 Azharites lived in every village until 50 years ago. They became mosque imams (prayer leaders), ma'zouns (public notaries), or just sheikhs if the family was prosperous. As a source of enlightenment, these figures enriched the village's cultural community," remarks Shalabi -- nostalgic, enthusiastic, disappointed that the present is so different. The relationship between Al-Azhar and the secular educational system was very vigorous, he recalls; the atmosphere was one of great tolerance, as the sheikhs and those who were described as "Westernised" considered, discussed, and accepted each other's opinions.

Thus did Azharites and secularly educated people gather every evening to socialise and engage in religious or literary discussions that were usually initiated by the interpretation of a certain Qur'anic verse, a term in a line of poetry, or an expression in a prophetic Hadith. The discussions would grow heated, and major sources -- Sahih Al-Bukhari, Tafsir Al-Galalin, Lisan Al-'Arab, Al-Misbah Al-Munir, Mukhtar Al-Sihah, Asfahani's Aghani, the Prolegomena of Ibn Khaldun, Al-Jahiz's Al-Bayan wal-Tabyin, Al-Hayawan, and Al-Bukhalaa, Abu Hayan Al-Tawhidi's Al-Imtaa' wal-Muanassa and Al-Asdiqaa, and Ibn Qutayba's Adab Al-Katib and Al-Ma'arif -- were summoned, until the authority of one author persuaded everyone of the validity of one argument or another.

The curious Shalabi found all these books in his uncle's library and read them, while on his own father's bookshelves he found political and contemporary literature. "Each man's library resembles him," he notes with a smile. From his father he inherited a passion for politicians' memoirs; he also listened avidly to numerous political conversations about the king, the parties, Lenin, Stalin, Roosevelt, Hitler, and Montgomery, who were all conjured up in the elders' discussions. Shalabi's secret preference, though, was for the Sira.

Each mandara had a few narrators of the Sira. At dawn, the story would be suspended at a particular point (usually a cliffhanger), and although the public had listened to and "lived through" the same events repeatedly, they were still possessed by an unquenchable thirst to hear how Abu Zeid Al-Hilali would escape from prison, for instance. This fascination preoccupied Shalabi from a very early age, because "it showed me how important popular story-telling was, how fiction and legend holds supreme sway in society," he comments. "All the respectable men sat there, full of curiosity and humility; their faces, the same faces that scared and terrified us, took on a child-like translucence as they listened and admired." The child could not help but love the magic this story-telling worked.

On receiving the primary school certificate at 12, Shalabi had already read over and over again the many written Siras: Al-Zir Salem, Al-Hilaliya, 'Antara, Zat Al-Himma, Hamza Al-Bahlawan, and Fayrouz Shah. By then, his narrative imagination had ripened. "I felt I could perceive the human beings behind the masks, and fathom the actual motives for human behaviour. I felt I saw the truth," he explains. Later, he sought to express this imagination in a powerful language, emulating the Sira, which to him, despite the colloquial terms that pervaded it, already seemed far more artistic than the high-brow language of his textbooks. He still believes the ideal literary language should be dramatic in its expression of ordinary life, ordinary people, and their thoughts and beliefs. Above all, he feels, this expression should not resemble the language of poetry, schoolbooks or official speeches.

The Sira, therefore, remained a major influence. Shalabi explains that it played an educational role besides that of entertainment. "Enlightened minds saturated these tales of war and adventure with moral values, such as chivalry and nationalism, that people could assimilate readily. In my opinion, and that of many others, our epics are superior to those of the Greeks, which are products of their reaction to legends, especially Ancient Egyptian mythology, that stretch across continents. The Egyptian popular epics, on the other hand, contain deeds deeply rooted in the national heritage." Shalabi regrets that it took so long before scholars like Abdel-Hamid Younes, whose research on the Sira did much to overturn the contempt with which it had been regarded by scholars, came along.

The main shortcoming of the educational system, in Shalabi's view, is the fact that we have translated, not created: "We merely Arabised the whole European syllabus." He believes this process alienated many generations from their cultural heritage, particularly in its oral forms. Shalabi, a language fanatic, points out that Cervantes admitted he was imitating the Arabic epics and adventures with which Andalucia's libraries were crammed, and that Boccaccio's Il Decamerone was an imitation of The Thousand and One Nights. The Renaissance absorbed Arab culture and then adapted it to Western sensibilities, he believes, thereby imposing rules upon narrative activity; yet "if we dig deeper into our own heritage we will find other rules, closer to our way of thinking and more appropriate for our culture". As for his own writing, Shalabi contends: "My complete non-reliance on Western literature is my chief contribution to contemporary Arabic literature."

Indeed, he only began to read Western literature after his narrative sensibility had already been shaped, and thus could easily perceive the influence of his indigenous heritage on European literature. Yet Shalabi is no cultural protectionist: he believes firmly that literature's highest humanist aspirations cannot be realised without a multiplicity of artistic nationalities and individual characters. "You can read a page and know -- regardless of names, terms or expressions -- that this is an Egyptian novel through the sensibility of its composition," he insists; any page in Yehia Haqqi's oeuvre, translated into any language, will still be recognised as purely Egyptian from the particularity of his vision and the way he relates to people and objects. "For instance, the way we relate to the Nile is different from another nation's manner of relating to its river," he elaborates. "The elements that make up a place shape the writer. If he is aware of them, he becomes a global writer, not because he writes about what interests the world's readers, but because a reader can find in his work a particularity: a special climate, aroma and taste."

After leaving his village, Shabas Omeir, in Kafr Al-Sheikh, Shalabi went to Damanhour to study at the Teachers' Institute. There, he met students from different backgrounds. "I saw their family roots in them," he remembers. He discovered the new literature, and a world beyond the works by Mahmoud Taymour, Taha Hussein, Abbas El-Aqqad, Lutfi El-Sayed, and Salama Moussa available in his village. His colleges at the institute helped publish his first book, each by paying for a copy in advance, in the late 1950s.

"My literature literally springs from the Egyptian street," Shalabi says. He believes it is his duty to bring people from the cities and villages to life in his novels and short stories. "If farmers, carpenters, mechanics, drivers, painters, tailors, barbers, and waiters could write, what would they write? Each must have his own relationships with objects, places and people," he muses. Shalabi himself worked all these trades at various stages of his life, and his first-person narration is rooted in real experience. He is very close to these characters; he tries to understand them fully. "I tell the stories of those I lived with. I share that responsibility. But I, too, am a victim -- of the lack of social unity, the loss of so many values, the chaos that envelopes us all in the end," he whispers.

Shalabi does not believe in subjectivity: "I'm not a severed individual 'self' in a vacuum. My life is not entirely my own." He is husband, father and writer at once, living and working in a particular place at a particular time; family, friends, and colleagues preclude the existence of a separate individual self. He opines that only in lyrical poetry can one express his inner voice -- "here, the artist must make subjective experience an objective entity, independent of its source".

Shalabi learned from his father's "mistakes"; despite the many political reversals of the time, he never held a political position, joined a political party, or wrote directly about politics. He never votes; to illustrate the fundamental incompatibility between politics and literature. He recalls that Naguib Mahfouz, long neglected because of his apolitical writing, was suddenly noticed by "the so-called Left, precisely because he did not represent their views! On the other hand, they dismissed his work as the writing of a government employee, and argued that only explicitly revolutionary literature was worthy of the title."

Voluntarily isolated from politics, he chose solitude, and for 20 years spent most of his waking hours in a cemetery. That is where he wrote his major novels. He rejected mainstream intellectual life: although in chronological terms he belongs to the "Sixties generation", he is not friends with many of its representatives. Yet his refusal to embrace political activity does not imply he is apathetic. "My beliefs include always being on side of the dispossessed, and I adhere to all humanist principles. I believe in everyone's right to education and prosperity." He is profoundly patriotic, and a fervent pan-Arabist: "I take pride in my history, and in the language and culture that offer me a new dimension in return for the historical depth of my belonging to Egypt."

Today, Shalabi still goes to the cemetery, but spends three days every week in the house where his family lives, and where he writes articles for various journals and magazines. The four remaining days he passes in his "cemetery office", which affords him the quiet he needs. As he writes or reads, he will smoke a shisha; his concentration only peaks around midnight, and he never goes to sleep before 8.00 or 9.00am.

He writes something every day, and spends four or five hours reading, now that his eyes cannot bear the strain of the eight or nine hours to which he was accustomed.

He considers Yehia Haqqi his literary father, Youssef Idris his older brother and Abdel-Rahman El-Sharqawi, Saad Mekkawi, Naguib Mahfouz, and Ihsan Abdel-Quddous his relatives. Nevertheless, he insists that "if I am stranded on a desert island for the rest of my life, the Thousand and One Nights will be quite enough."

Select bibliography

Novels:

Al-Sanyura (Signora)

Al-Awbash (Scoundrels)

Al-Watad (Tent Peg)

Far'an min Al-Sabbar (Two Cactus Branches)

Al-Arawi (Buttonholes)

Al-Amali (The Amali Trilogy)

Al-Shuttar (The Clever Ones)

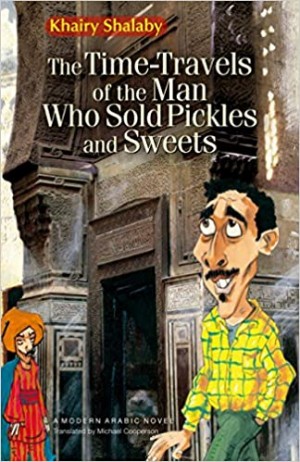

Rahalat Al-Turshagi Al-Halwagi (Journeys of the Pickle and Dessert Maker)

Wikalat Attiya (Attiya's Wikala)

Mawwal Al-Bayat wal-Noum (Ballad of Shelter and Sleep)

Baghlat Al-'Arsh (The Throne's Mule)

Batn Al-Baqara (The Cow's Belly)

Short story collections:

Asbab lil-Kay bil-Nar (Reasons to be Burned)

Sahib Al-Sa'ada Al-Liss (His Majesty the Thief)

Al-Munhana Al-Khatar (Dangerous Turn)

Lahs Al-'Atab (Licking the Threshold)

Sareq Al-Farah (The Wedding Thief)

Mawt 'Aba'a (Death of a Cloak)