Albert Camus (7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, and journalist. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44 in 1957, the second youngest recipient in history.

Camus was born in Algeria to French parents. He spent his childhood in a poor neighbourhood and later studied philosophy at the University of Algiers. He was in Paris when the Germans invaded France during World War II. Camus tried to flee but finally joined the French Resistance where he served as editor-in-chief at Combat, an outlawed newspaper. After the war, he was a celebrity figure and gave many lectures around the world. He married twice but had many extramarital affairs. Camus was politically active. He was part of the Left that opposed the Soviet Union because of its totalitarianism. Camus was a moralist and was leaning towards anarcho-syndicalism. He was part of many organisations seeking European integration. During the Algerian War, he kept a neutral stance advocating for a multicultural and pluralistic Algeria, a position that caused controversy and was rejected by most parties.

Philosophically, Camus‘s views contributed to the rise of the philosophy known as absurdism. He is also considered to be an existentialist, despite his having firmly rejected the term throughout his lifetime.

Camus’s first publication was a play Revolte dans les Asturies (Revolt in the Asturias) written with three friends in May 1936. The subject was the 1934 revolt by Spanish miners that was brutally suppressed by the Spanish government resulting in 1,500 to 2,000 deaths. In May 1937 he wrote his first book, L’Envers et l’Endroit (Betwixt and Between also translated as The Wrong Side and the Right Side). Both were published by Edmond Charlot’s small publishing house.

Camus crowning Stockholm’s Lucia on 13 December 1957, three days after accepting the Nobel Prize in Literature

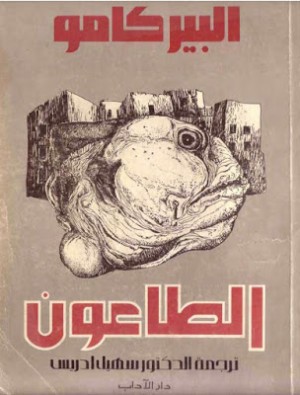

Camus separated his work into three cycles. Each cycle consisted of a novel, an essay, and a play. The first was the cycle of the absurd consisting of L’Étranger, Le Mythe de Sysiphe and Caligula. The second was the cycle of the revolt which included La Peste (The Plague), L’Homme révolté (The Rebel) and Les Justes (The Just Assassins). The third, the cycle of the love, consisted of Nemesis. Each cycle was an examination of a theme with the use of a pagan myth and including biblical motifs.

The books in the first cycle were published between 1942 and 1944, but the theme was conceived earlier, at least as far back as 1936.[33] With this cycle, Camus aims to pose a question on the human condition, discuss the world as an absurd place, and warn humanity of the consequences of totalitarianism.

Camus began his work on the second cycle while he was in Algeria, in the last months of 1942, just as the Germans were reaching North Africa.[35] In the second cycle, Camus used Prometheus, who is depicted as a revolutionary humanist, to highlight the nuances between revolution and rebellion. He analyses various aspects of rebellion, its metaphysics, its connection to politics, and examines it under the lens of modernity, of historicity and the absence of a God.

After receiving the Nobel Prize award, Camus gathered, clarified, and published his pacifist leaning views at Actuelles III: Chronique algérienne 1939–1958 (Algerian Chronicles). He then decided to distance himself from the Algerian War as he found the mental burden too heavy. He turned to theatre and the third cycle which was about love and the goddess Nemesis.

Two of Camus’s works were published posthumously. The first entitled La mort heureuse (A Happy Death) (1970), features a character named Patrice Mersault, comparable to The Stranger‘s Meursault. There is scholarly debate about the relationship between the two books. The second was an unfinished novel, Le Premier homme (The First Man) (1995), which Camus was writing before he died. It was an autobiographical work about his childhood in Algeria.

The publication of this book in 1994 has sparked a widespread reconsideration of Camus’s allegedly unrepentant colonialism.