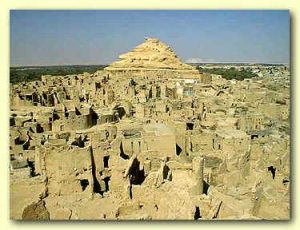

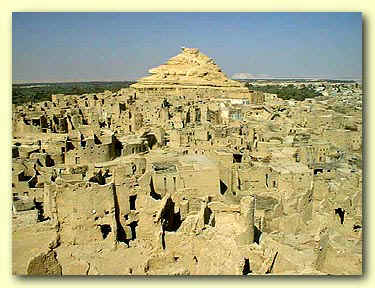

Siwa, once the most mysterious of all Egypt's oases, is also the most fascinating. It's history has not only been shaped by all major civilisations, but also by the contrast of the surrounding desert with the lush soil of the oasis setting. Siwa, like other Western Oasis, has had a number of different names over the millenniums. It was called Santariya by the ancient Arabs, as well as the Oasis of Jupiter-Amun, Marmaricus Hammon, the Field of Palm Trees and Santar by the ancient Egyptians. It is believed to have been occupied as early as Paleolithic and Neolithic times, and some believe it was the capital of an ancient kingdom that may have included Qara, Arashieh and Bahrein. During Egypt's Old Kingdom, it was a part of Tehenu, the Olive Land that may have extended as for east as Mareotis. Aside from that, the Siwa Oasis has little in common with the other Western Oasis. The Siwan people are mostly Berbers, the true Western Desert indigenous people, who once roamed the North African coast between Tunisia and Morocco. They have their own culture and customs and, as well as speaking Arabic, speak own Berber (Amazigh) language. Women still wear traditional costumes and silver jewellery.  The modern town of Siwa is set among thick palm groves, walled gardens and olive orchards, with numerous freshwater springs and salt lakes. Siwa also clusters beneath the impressive remains of the ancient fortress town of Shali. Actually almost nothing is known of the Siwa Oasis during Egypt's ancient history. It was not until the beginning of the 26th Dynasty that there was any evidence that Siwa was infact part of the Egyptian empire. It was then that the Gebel el-Mawta Necropolis was established, which was in use through the Roman Period. In fact, some sources maintain that it remained an independed Sheikhdom ruled by a Libyan tribal chief until Roman times. The two temples that we know of, both dedicated to Amun, were established by Ahmose II and Nectanebo II. Yet just exactly how integrated it was in the Egyptian realm is questionable. One of the most notable and interesting stories in Egyptian history involves Cambyses II, who apparently had problems with the Oasis. He sent an army to the Oasis in order to seize control, but the entire caravan was lost to the desert, never arriving at Siwa. To this day, the event remains a mystery, though tantalizing clues seem to be popping up. It was the Greeks who made the Siwa Oasis notable. After having established themselves in Cyrene (in modern Libya) they discovered and popularized the Oracle of Amun located in the Siwa Oasis, and at least one of the greatest stories told of the Oasis concerns the visit by Alexander the Great to the Oracle. Almost immediately after taking Egypt from the Persians and establishing Alexandria, Alexander the Great headed for the Siwa Oasis to consult the now famous Oracle of Amun. This trip, made with a few comrades, is well documented. He was not the first to experience problems in the desert, as whole armies before him had been lost in the sand. The caravan got lost, ran out of water and was even caught up in an unusual rainstorm. However, upon arrival at the Oasis and the Oracle of Amun, Alexander was pronounced a god, an endorsement required for legitimate rule of the country.

The modern town of Siwa is set among thick palm groves, walled gardens and olive orchards, with numerous freshwater springs and salt lakes. Siwa also clusters beneath the impressive remains of the ancient fortress town of Shali. Actually almost nothing is known of the Siwa Oasis during Egypt's ancient history. It was not until the beginning of the 26th Dynasty that there was any evidence that Siwa was infact part of the Egyptian empire. It was then that the Gebel el-Mawta Necropolis was established, which was in use through the Roman Period. In fact, some sources maintain that it remained an independed Sheikhdom ruled by a Libyan tribal chief until Roman times. The two temples that we know of, both dedicated to Amun, were established by Ahmose II and Nectanebo II. Yet just exactly how integrated it was in the Egyptian realm is questionable. One of the most notable and interesting stories in Egyptian history involves Cambyses II, who apparently had problems with the Oasis. He sent an army to the Oasis in order to seize control, but the entire caravan was lost to the desert, never arriving at Siwa. To this day, the event remains a mystery, though tantalizing clues seem to be popping up. It was the Greeks who made the Siwa Oasis notable. After having established themselves in Cyrene (in modern Libya) they discovered and popularized the Oracle of Amun located in the Siwa Oasis, and at least one of the greatest stories told of the Oasis concerns the visit by Alexander the Great to the Oracle. Almost immediately after taking Egypt from the Persians and establishing Alexandria, Alexander the Great headed for the Siwa Oasis to consult the now famous Oracle of Amun. This trip, made with a few comrades, is well documented. He was not the first to experience problems in the desert, as whole armies before him had been lost in the sand. The caravan got lost, ran out of water and was even caught up in an unusual rainstorm. However, upon arrival at the Oasis and the Oracle of Amun, Alexander was pronounced a god, an endorsement required for legitimate rule of the country.  Cleopatra VII may have also visited this Oasis to consult with the Oracle, as well as perhaps bathe in the spring that now bears her name. However, by the Roman period, Augustus sent political prisoners to the Siwa so it too, like the other desert oasis, became a place of banishment. Christianity would have had a difficult time establishing itself in this Oasis, and most sources agree that it did not. However, Bayle St. John says that in fact the Temple of the Oracle was actually turned into the Church of the Virgin Mary. This is understandable given that along with political prisoners, the Romans banished church leaders to the Western Oasis, including, Athanasius tells us, to Siwa. In fact, we find that during the Byzantine era it probably belonged to the dioceses of the Libyan eparchy. However, no real record, or for that matter, archaeological evidence exists to support Christianity in the Oasis. By 708 AD, Islam came to the Oasis. Though earlier than some of the other Western Oasis, it had little success at first. The Siwans may have been Christian at this point, but regardless, they withdrew to their fortress and fought valiantly against the invading forces of Musa Ibn Nusayr, finally repelling his army. Next came Tariq Ibn Ziyad of Spain, but his army was also defeated. Though some sources disagree, it was probably not until 1150 AD that Islam finally took hold in the Siwa Oasis. However, by 1203 we are told that the population of the Siwa Oasis had declined to as low as 40 men from seven families due to constant attacks and particularly after a rather viscous Bedouin assault. In order to found a more secure settlement, they moved from the ancient town of Aghurmi and established the present city called Shali, which simply means town. This new fortified town was built with only three gates. An Islamic historian, Maqrizi, explains that soon after there were 600 people living in the Oasis. At this point the Siwa may have been an independent republic. He goes on to say that it was populated by strange and fearsome animals and that the people were plagued by unusual diseases. However, he also says of the Siwa that its fertility was legendary, citing an "orange-tree as large as an Egyptian sycamore, producing fourteen thousand oranges every year". The Siwa exported crops to Egypt and Cyrene. One of the main historical references we have on the Siwa Oasis is called the "Siwan Manuscript" which was written during the middle ages and serves as a local history book. It tells us of a benevolent man who arrived in the Oasis and planted an orchard. Afterward, he went to Mecca and brought back thirsty Arabs and Berbers to live in the Oasis, where he established himself, along with his followers in the western part of Shali. Unfortunately, there seems to have almost immediately been problems between the original inhabitants, who were later known as the Easterners, and the new families western families who to this day are proud to be described as "The Thirty". The conflicts between the two sides became legendary, and sometimes rose into short, but intense violence. An example comes to us from C. Dalrymple Belgrave, who describes an incident caused by an Easterner who wished to enlarge his house. This addition would have encroached upon the already narrow street, so "The Thirty" objected. He goes on to tell us of a typical outburst: "A Sheikh sounded a drum as a declaration of hostilities. The combatants then assembled to fight the battle with their advisories. The women stood behind their husbands to excite their courage; each of whom had a sack of stones in her hand, to cast at the enemy, and even at those of their own party who should be tempted to fly before the close of the combat. At the beat of the drum, small platoons advanced successively from both sides, rushing furiously toward each other. they never placed their guns to the shoulder, but fired carelessly with their arms extended, and then retired. No person was allowed to fire his gun more than once; and when all had thus performed their part, whatever might be the number of dead or wounded, the Sheikh beat his drum, and the combat ceased." Obviously, if the Siwans could not get along with each other, they must surely have had trouble accepting outsiders. The first European we know of to visit the Siwa Oasis was W. G. Browne, who accompanied a date caravan and disguised himself as an Arab. He hoped to find the famous site of the Oracle of Amun. However, he was found out and had to remain indoors to avoid problems. On the fourth day of his visit he was finally allowed to venture out, only to be disappointed when he actually found the temple, thinking it too small to to be of much importance. Then came Frederick Hornemann, a German with the African Association. Also accompanying a date caravan in disguise, he managed to fool the locals for eight days. However, he was found out and chased through the desert. Though he managed to escape, his interpreter ran off with Hornemann's plundered artifacts, mineral specimens and expedition notes, supposedly burying them in the desert where they remain today. When, in 1819, Muhammad Ali, the founder of modern Egypt, began his conquest of the Western Oasis, he sent between 1,300 and 2,000 troops to the Siwa Oasis under the the commander, Hassan Bey Shamashurghi. The ensuing battle lasted for three hours, but the Siwans this time were no match for modern artillery. They had to yield to this superior force, and were forced to pay a tribute of some 2,000 pounds, a significant amount in those days and particularly to the Siwans who had little hard currency. Along with Shamashurghi came the French Consul Bernardino Drovetti, along with the artist and engineer, Louis Linant de Bellefonds, a pharmacist named Enegildo Frediani and others. They tell us of more antiquities located in the Oasis than we see today, and in 1834, information regarding the Siwan language was found among Drovetti's notes and published by Jomard. Also, Frediani published his own letters, and in some instances, these records are our only source of information for this period. That same year, Frederic Caillaud, a mineralogist and also an envoy of the Pasha, along with Pierre Letorzec, a French sailor, visited the Oasis. They investigated the tombs at Gebel Mawta and other antiquities west of the Oasis, and after bribing the locals, were also allowed a visit to the temple of the Oracle. The results of this visit was the first scientific report on the Siwa Oasis, including the fact that it was below sea level. Cailliaud also published a book and a 470 word lexicon on the Siwan language. What we know of the Umm Ubayd Temple, which was later destroyed, comes from a visit by the Prussian Heinrich Von Minutoli when he visited the Oasis in September of 1820. He made detailed illustrations and accounts of the antiquities all about the Siwa. However, matters were not settled in the Oasis as for the distant rule of Muhammad Ali. It seems there was a repetition of him sending troops, the people of the Siwa resisting, then giving in and agreeing to pay tribute, but once the troops were gone, reneging and refusing to allow strangers into their community, so Muhammad Ali would once again send troops. Finally, in 1829, the Pasha sent 600 to 800 soldiers who conquered the Siwa, along with a ruthless governor by the name of Hasan Bey. He had eighteen Sheikhs executed and twenty others banished. He increased the tribute, and confiscated money, slaves, dates and silver as payment for the back debt. He was also responsible for building the first markaz, a government office, behind Qasr Hassuna. By about 1834, The Siwa Oasis was considered to be safe for travel, and perhaps for a time it was, because a number of people did visit including Bayle St. John, and English adventurer who stayed for some time. He published a book in 1849, called "Adventures in the Libyan Desert", that provides fine information on the Oasis during that period. He was allowed to visit the gardens and the Temple of the Oracle, but interestingly, was not allowed inside Shali proper. However, when James Hamilton visited the Oasis in 1852, his camp was invaded and he was taken as a virtual prisoner by Yusif Ali, a zaggala. However, Hamilton managed to smuggle out several letters, and on March 14th 1852, 150 Calvary with fourteen officers went to the Oasis, and within a week, Hamilton was escorted out of the Oasis by Yusif Ali. Now this was an interesting situation, because when Siwan dignitaries failed to appear in Cairo as promised to explain their conduct regarding Hamilton, the viceroy sent 200 men to the oasis who made life very difficult. They committed robbery, stole women and shot anyone who spoke out. Yet, Yousef Ali was himself finally made governor of the Oasis, apparently by turning against the locals. Then, in 1854 under a new ruler of Egypt, those imprisoned by Ali were set free, and returned to the Oasis. They immediately went after Ali, who escaped, was caught again and finally killed. In 1869 and again in 1874, Gerhard Rohlfs visited the oasis and discovered the reason why the Siwans continued to have troubles with Cairo. It turns out that the Sanusi, a power force within the Libyan desert made up of a religious order established by Al-Sayyid Muhammad bin Ali al-Sanusi Khatibi al-Idrisi al-Hasani, had told the Siwans not to pay their taxes. The Sanuis opposed contact with the west, and were viewed as a threat by Europeans. They had also established themselves early on in this oasis. Hence, the locals were placed in a difficult situation, between the ruling powers of Egypt and the Sanuis who represented a real power within the desert. This matter seems not to have been resolved, perhaps, until at least the First World War. In 1898, we find a new tale that seems almost to come from the hand of Shakespeare out of the pages of Romeo and Juliet. It was called the Widow's War, for following the death of the local mayor (umda) of Siwa, his young wife wished to marry again. An Easterner, she wanted to marry one of "The Thirty", a Westerner. However, her stepson decided she should marry another, so she fled to Uthman Haban, a Sanusi (and Westerner), apparently for protection. This started the war drums, so she then returned to her stepson only to disappear again the next day. She had gone to her Westerner lover, but her stepson apparently seized her and forced her to marry the man of his choosing. The whole village seemed to have been in an uproar over the whole matter, and two men were killed. The war drums started once more, but a small boy was shot by mistake and a truce was called. However, this did not last long, and after the Easterners attacked a spring, Belgrave tells us that: "Then the entire Western force, led by their chief, Uthman Habun, on his great white war-horse, the only one in Siwa, surged out of the town, through the narrow gates, firing and shrieking, waving swards and spears, followed by their women throwing stones. Every able bodied man and woman joined in the battle beneath the walls...'The Habun' found himself in danger of being captured...Habun's mother, seeing her son in danger, collected a dozen women of his house and managed to get near him. He left his horse and slipped into the gardens where he joined the women. They dressed him as a girl, and with them he escaped to the tomb of Sidi Suliman. Habun sent to the Sanusi at Jugbub and they created the peace. This pattern of sporadic, but regular violence continued until the Sanusi created order." The Sanusi continued to dominate the Oasis for many years, and it was a popular crossing for their caravans, particularly those transporting slaves from Kufra. The locals helped in this endeavor, and many of the slaves remained in the Siwa, where many of their descendents remain today. Within the 20th Century, the first Egyptian ruler to visit the Siwa Oasis was Abbas II, but even he had to disguise his Austrian wife as an Egyptian army officer. He went there in style, with a vanguard consisting of 62 camels and a main entourage of 228 camels and 22 horses. Water was carried from Cairo in 120 iron chests, as Abbas rode along in his fine carriage. He received a warm welcome from the residence, who meet him waving palm branches while musicians played and banners fluttered. To honor his visit, the local Khedive even laid the foundation for a new mosque. It would seem that the Siwa was finally becoming a part of modern Egypt. Afterwards, the Oasis saw considerable activity with a number of visitors including the renowned Oasis Egyptologist, Ahmed Fakhry. Yet, the two world wars would cause considerable problems for the Oasis. The Siwa was really caught up between opposing forces during World War I. Now, the Siwans found themselves in the middle of the Italians who had colonized Libya and the Sanusi, who they were most sympathetic to and who had sided with the Turks on the one hand, and the British who had colonized Egypt on the other. After several failed attempts, the Sanusi, who had already entered Farafra and Bahariya in February of 1916, finally also occupied the Siwa on April 1st. While the other Oasis rapidly fell to the British, they did not take the Siwa until February 5th of 1917. During all this time, the Siwans managed to survive by moving into the tombs of Gebel al-Mawta and simply welcoming whichever invader was in town at the time. Massy, in "The Desert Campaigns" tells us of the battle. It was February 1st, 1917 that the British took to the desert from Mersa Matruh. According to Massy, the force consisted of: "Rolls Royce armoured cars, Talbot wagons, Ford Light patrol and supply cars, a Daimler lorry carrying a Krupp gun made in 1871, and captured from the enemy in 19165, and over a score of motor lorries." Then, about 90 miles from the escarpment, General Hodgson sent out a reconnaissance to find Qirba, some low hills were it was believed the enemy was hiding. They were found, and at noon the Sanusi attempted a charge. However, the British machine guns and heavy motorized vehicles were too much for the Sanusi's two ten pound cannons, two machine guns and 800 small arms. All the following night there was sniper fire, and then in the morning the Sanusi fired two last cannon shells and after throwing their ammunition on a fire, retreated. When the British entered the Siwa, they were warmly received and by February 8th, the whole matter was finished. During the remainder of the war, the Siwa became a tourist attraction with tours et up by Captain Hillier, a former member of the Frontier District Administration who set up trips through the Libyan Oasis Association of Alexandria. This was the beginning of real tourism to the Oasis, and visitors had their choice between a nine day tour by rail and coach from Mersa Matruh or a month long camel safari that connected with the Wadi Natrun and the Qattara Depression. Hillier had set up a small, two story hotel on the spur of the Gebel al-Mawta called the Prince Farouk Hotel. Though the whitewashed mudbrick structure could only hold about twelve guests, they had access to a dining room, lounge and verandah. In 1926, when, after three days and nights, the rain bead down on the salt caked mud houses of Shali, the old town was made mostly uninhabitable and residence were eventually forced to move into new housing outside the old city. During World War II, Siwa again played an important role. Most of that war saw the Siwa occupied with Allied troops consisting mainly of British, Australians and New Zealanders. It was closed to none military visitors. However, it was bombed by the Italians who had occupied Libya, killing 100 people (and a donkey, we are told), and later, the Germans had their turn in the Oasis. Even Field Marshal Rommel visited, but it was later retaken by the Allies. Afterwards, visitation to the Siwa was restricted for a number of years. Today, the Siwa, while not a heavily trafficked tourist destination, welcomes those that it receives. It offers restaurants, craft shops as well as some nice hotels and great desert tours. Furthermore, in the fall of 1997, an ecolodge was built by the Environmental Sustainable Tourism Program as a joint effort of USAID and the Ford Foundation and we now find a number of interesting resorts within this once forsaken land. The town now even supports a renovated airport.

Cleopatra VII may have also visited this Oasis to consult with the Oracle, as well as perhaps bathe in the spring that now bears her name. However, by the Roman period, Augustus sent political prisoners to the Siwa so it too, like the other desert oasis, became a place of banishment. Christianity would have had a difficult time establishing itself in this Oasis, and most sources agree that it did not. However, Bayle St. John says that in fact the Temple of the Oracle was actually turned into the Church of the Virgin Mary. This is understandable given that along with political prisoners, the Romans banished church leaders to the Western Oasis, including, Athanasius tells us, to Siwa. In fact, we find that during the Byzantine era it probably belonged to the dioceses of the Libyan eparchy. However, no real record, or for that matter, archaeological evidence exists to support Christianity in the Oasis. By 708 AD, Islam came to the Oasis. Though earlier than some of the other Western Oasis, it had little success at first. The Siwans may have been Christian at this point, but regardless, they withdrew to their fortress and fought valiantly against the invading forces of Musa Ibn Nusayr, finally repelling his army. Next came Tariq Ibn Ziyad of Spain, but his army was also defeated. Though some sources disagree, it was probably not until 1150 AD that Islam finally took hold in the Siwa Oasis. However, by 1203 we are told that the population of the Siwa Oasis had declined to as low as 40 men from seven families due to constant attacks and particularly after a rather viscous Bedouin assault. In order to found a more secure settlement, they moved from the ancient town of Aghurmi and established the present city called Shali, which simply means town. This new fortified town was built with only three gates. An Islamic historian, Maqrizi, explains that soon after there were 600 people living in the Oasis. At this point the Siwa may have been an independent republic. He goes on to say that it was populated by strange and fearsome animals and that the people were plagued by unusual diseases. However, he also says of the Siwa that its fertility was legendary, citing an "orange-tree as large as an Egyptian sycamore, producing fourteen thousand oranges every year". The Siwa exported crops to Egypt and Cyrene. One of the main historical references we have on the Siwa Oasis is called the "Siwan Manuscript" which was written during the middle ages and serves as a local history book. It tells us of a benevolent man who arrived in the Oasis and planted an orchard. Afterward, he went to Mecca and brought back thirsty Arabs and Berbers to live in the Oasis, where he established himself, along with his followers in the western part of Shali. Unfortunately, there seems to have almost immediately been problems between the original inhabitants, who were later known as the Easterners, and the new families western families who to this day are proud to be described as "The Thirty". The conflicts between the two sides became legendary, and sometimes rose into short, but intense violence. An example comes to us from C. Dalrymple Belgrave, who describes an incident caused by an Easterner who wished to enlarge his house. This addition would have encroached upon the already narrow street, so "The Thirty" objected. He goes on to tell us of a typical outburst: "A Sheikh sounded a drum as a declaration of hostilities. The combatants then assembled to fight the battle with their advisories. The women stood behind their husbands to excite their courage; each of whom had a sack of stones in her hand, to cast at the enemy, and even at those of their own party who should be tempted to fly before the close of the combat. At the beat of the drum, small platoons advanced successively from both sides, rushing furiously toward each other. they never placed their guns to the shoulder, but fired carelessly with their arms extended, and then retired. No person was allowed to fire his gun more than once; and when all had thus performed their part, whatever might be the number of dead or wounded, the Sheikh beat his drum, and the combat ceased." Obviously, if the Siwans could not get along with each other, they must surely have had trouble accepting outsiders. The first European we know of to visit the Siwa Oasis was W. G. Browne, who accompanied a date caravan and disguised himself as an Arab. He hoped to find the famous site of the Oracle of Amun. However, he was found out and had to remain indoors to avoid problems. On the fourth day of his visit he was finally allowed to venture out, only to be disappointed when he actually found the temple, thinking it too small to to be of much importance. Then came Frederick Hornemann, a German with the African Association. Also accompanying a date caravan in disguise, he managed to fool the locals for eight days. However, he was found out and chased through the desert. Though he managed to escape, his interpreter ran off with Hornemann's plundered artifacts, mineral specimens and expedition notes, supposedly burying them in the desert where they remain today. When, in 1819, Muhammad Ali, the founder of modern Egypt, began his conquest of the Western Oasis, he sent between 1,300 and 2,000 troops to the Siwa Oasis under the the commander, Hassan Bey Shamashurghi. The ensuing battle lasted for three hours, but the Siwans this time were no match for modern artillery. They had to yield to this superior force, and were forced to pay a tribute of some 2,000 pounds, a significant amount in those days and particularly to the Siwans who had little hard currency. Along with Shamashurghi came the French Consul Bernardino Drovetti, along with the artist and engineer, Louis Linant de Bellefonds, a pharmacist named Enegildo Frediani and others. They tell us of more antiquities located in the Oasis than we see today, and in 1834, information regarding the Siwan language was found among Drovetti's notes and published by Jomard. Also, Frediani published his own letters, and in some instances, these records are our only source of information for this period. That same year, Frederic Caillaud, a mineralogist and also an envoy of the Pasha, along with Pierre Letorzec, a French sailor, visited the Oasis. They investigated the tombs at Gebel Mawta and other antiquities west of the Oasis, and after bribing the locals, were also allowed a visit to the temple of the Oracle. The results of this visit was the first scientific report on the Siwa Oasis, including the fact that it was below sea level. Cailliaud also published a book and a 470 word lexicon on the Siwan language. What we know of the Umm Ubayd Temple, which was later destroyed, comes from a visit by the Prussian Heinrich Von Minutoli when he visited the Oasis in September of 1820. He made detailed illustrations and accounts of the antiquities all about the Siwa. However, matters were not settled in the Oasis as for the distant rule of Muhammad Ali. It seems there was a repetition of him sending troops, the people of the Siwa resisting, then giving in and agreeing to pay tribute, but once the troops were gone, reneging and refusing to allow strangers into their community, so Muhammad Ali would once again send troops. Finally, in 1829, the Pasha sent 600 to 800 soldiers who conquered the Siwa, along with a ruthless governor by the name of Hasan Bey. He had eighteen Sheikhs executed and twenty others banished. He increased the tribute, and confiscated money, slaves, dates and silver as payment for the back debt. He was also responsible for building the first markaz, a government office, behind Qasr Hassuna. By about 1834, The Siwa Oasis was considered to be safe for travel, and perhaps for a time it was, because a number of people did visit including Bayle St. John, and English adventurer who stayed for some time. He published a book in 1849, called "Adventures in the Libyan Desert", that provides fine information on the Oasis during that period. He was allowed to visit the gardens and the Temple of the Oracle, but interestingly, was not allowed inside Shali proper. However, when James Hamilton visited the Oasis in 1852, his camp was invaded and he was taken as a virtual prisoner by Yusif Ali, a zaggala. However, Hamilton managed to smuggle out several letters, and on March 14th 1852, 150 Calvary with fourteen officers went to the Oasis, and within a week, Hamilton was escorted out of the Oasis by Yusif Ali. Now this was an interesting situation, because when Siwan dignitaries failed to appear in Cairo as promised to explain their conduct regarding Hamilton, the viceroy sent 200 men to the oasis who made life very difficult. They committed robbery, stole women and shot anyone who spoke out. Yet, Yousef Ali was himself finally made governor of the Oasis, apparently by turning against the locals. Then, in 1854 under a new ruler of Egypt, those imprisoned by Ali were set free, and returned to the Oasis. They immediately went after Ali, who escaped, was caught again and finally killed. In 1869 and again in 1874, Gerhard Rohlfs visited the oasis and discovered the reason why the Siwans continued to have troubles with Cairo. It turns out that the Sanusi, a power force within the Libyan desert made up of a religious order established by Al-Sayyid Muhammad bin Ali al-Sanusi Khatibi al-Idrisi al-Hasani, had told the Siwans not to pay their taxes. The Sanuis opposed contact with the west, and were viewed as a threat by Europeans. They had also established themselves early on in this oasis. Hence, the locals were placed in a difficult situation, between the ruling powers of Egypt and the Sanuis who represented a real power within the desert. This matter seems not to have been resolved, perhaps, until at least the First World War. In 1898, we find a new tale that seems almost to come from the hand of Shakespeare out of the pages of Romeo and Juliet. It was called the Widow's War, for following the death of the local mayor (umda) of Siwa, his young wife wished to marry again. An Easterner, she wanted to marry one of "The Thirty", a Westerner. However, her stepson decided she should marry another, so she fled to Uthman Haban, a Sanusi (and Westerner), apparently for protection. This started the war drums, so she then returned to her stepson only to disappear again the next day. She had gone to her Westerner lover, but her stepson apparently seized her and forced her to marry the man of his choosing. The whole village seemed to have been in an uproar over the whole matter, and two men were killed. The war drums started once more, but a small boy was shot by mistake and a truce was called. However, this did not last long, and after the Easterners attacked a spring, Belgrave tells us that: "Then the entire Western force, led by their chief, Uthman Habun, on his great white war-horse, the only one in Siwa, surged out of the town, through the narrow gates, firing and shrieking, waving swards and spears, followed by their women throwing stones. Every able bodied man and woman joined in the battle beneath the walls...'The Habun' found himself in danger of being captured...Habun's mother, seeing her son in danger, collected a dozen women of his house and managed to get near him. He left his horse and slipped into the gardens where he joined the women. They dressed him as a girl, and with them he escaped to the tomb of Sidi Suliman. Habun sent to the Sanusi at Jugbub and they created the peace. This pattern of sporadic, but regular violence continued until the Sanusi created order." The Sanusi continued to dominate the Oasis for many years, and it was a popular crossing for their caravans, particularly those transporting slaves from Kufra. The locals helped in this endeavor, and many of the slaves remained in the Siwa, where many of their descendents remain today. Within the 20th Century, the first Egyptian ruler to visit the Siwa Oasis was Abbas II, but even he had to disguise his Austrian wife as an Egyptian army officer. He went there in style, with a vanguard consisting of 62 camels and a main entourage of 228 camels and 22 horses. Water was carried from Cairo in 120 iron chests, as Abbas rode along in his fine carriage. He received a warm welcome from the residence, who meet him waving palm branches while musicians played and banners fluttered. To honor his visit, the local Khedive even laid the foundation for a new mosque. It would seem that the Siwa was finally becoming a part of modern Egypt. Afterwards, the Oasis saw considerable activity with a number of visitors including the renowned Oasis Egyptologist, Ahmed Fakhry. Yet, the two world wars would cause considerable problems for the Oasis. The Siwa was really caught up between opposing forces during World War I. Now, the Siwans found themselves in the middle of the Italians who had colonized Libya and the Sanusi, who they were most sympathetic to and who had sided with the Turks on the one hand, and the British who had colonized Egypt on the other. After several failed attempts, the Sanusi, who had already entered Farafra and Bahariya in February of 1916, finally also occupied the Siwa on April 1st. While the other Oasis rapidly fell to the British, they did not take the Siwa until February 5th of 1917. During all this time, the Siwans managed to survive by moving into the tombs of Gebel al-Mawta and simply welcoming whichever invader was in town at the time. Massy, in "The Desert Campaigns" tells us of the battle. It was February 1st, 1917 that the British took to the desert from Mersa Matruh. According to Massy, the force consisted of: "Rolls Royce armoured cars, Talbot wagons, Ford Light patrol and supply cars, a Daimler lorry carrying a Krupp gun made in 1871, and captured from the enemy in 19165, and over a score of motor lorries." Then, about 90 miles from the escarpment, General Hodgson sent out a reconnaissance to find Qirba, some low hills were it was believed the enemy was hiding. They were found, and at noon the Sanusi attempted a charge. However, the British machine guns and heavy motorized vehicles were too much for the Sanusi's two ten pound cannons, two machine guns and 800 small arms. All the following night there was sniper fire, and then in the morning the Sanusi fired two last cannon shells and after throwing their ammunition on a fire, retreated. When the British entered the Siwa, they were warmly received and by February 8th, the whole matter was finished. During the remainder of the war, the Siwa became a tourist attraction with tours et up by Captain Hillier, a former member of the Frontier District Administration who set up trips through the Libyan Oasis Association of Alexandria. This was the beginning of real tourism to the Oasis, and visitors had their choice between a nine day tour by rail and coach from Mersa Matruh or a month long camel safari that connected with the Wadi Natrun and the Qattara Depression. Hillier had set up a small, two story hotel on the spur of the Gebel al-Mawta called the Prince Farouk Hotel. Though the whitewashed mudbrick structure could only hold about twelve guests, they had access to a dining room, lounge and verandah. In 1926, when, after three days and nights, the rain bead down on the salt caked mud houses of Shali, the old town was made mostly uninhabitable and residence were eventually forced to move into new housing outside the old city. During World War II, Siwa again played an important role. Most of that war saw the Siwa occupied with Allied troops consisting mainly of British, Australians and New Zealanders. It was closed to none military visitors. However, it was bombed by the Italians who had occupied Libya, killing 100 people (and a donkey, we are told), and later, the Germans had their turn in the Oasis. Even Field Marshal Rommel visited, but it was later retaken by the Allies. Afterwards, visitation to the Siwa was restricted for a number of years. Today, the Siwa, while not a heavily trafficked tourist destination, welcomes those that it receives. It offers restaurants, craft shops as well as some nice hotels and great desert tours. Furthermore, in the fall of 1997, an ecolodge was built by the Environmental Sustainable Tourism Program as a joint effort of USAID and the Ford Foundation and we now find a number of interesting resorts within this once forsaken land. The town now even supports a renovated airport.

Sources: Egypt Website

Tour Egypt Website

Siwa Oasis Website

Genna Alsaegh - منذ 5 أشهر

Thank You! This was a fascinating read!