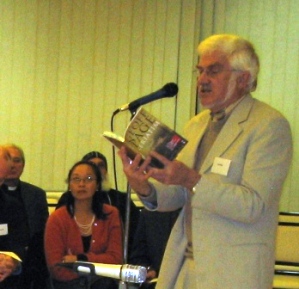

Geoff Page

Geoff Page is an Australian poet who has published eighteen collections of poetry as well as two novels, four verse novels and several other works including anthologies, translations and a biography of the jazz musician, Bernie McGann. He retired at the end of 2001 from being in charge of the English Department at Narrabundah College in the ACT, a position he had held since 1974. He has won several awards, including the ACT Poetry Award, the Grace Leven Prize, the Christopher Brennan Award, the Queensland Premier’s Prize for Poetry and the 2001 Patrick White Literary Award. Selections from his work have been translated into Chinese, German, Serbian, Slovenian and Greek. He has also read his work and talked on Australian poetry in Switzerland, Germany, Norway, Sweden, Britain, Italy, Spain, Serbia, Slovenia, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Austria, Hungary, Singapore, China, Korea, the United States and New Zealand. This is a selection of the poems he read in the evening in Canberra.

Arthur Phillip

Why is it dreams are like our history,

two parts pride and two parts shame?

First in the world with secret ballot,

slow to give murder a working name.

Can it be we’re still a dream

disrupting Arthur Phillip’s sleep.

Inside that eighteenth century head

we’re convicts, whipped, who will not weep

or ‘Native Aboriginees’

too primal to salute the king —

who greets us all with half a wave

and hopes that we’re not suffering.

Transported dreams bestowed the vote

and, later, all that kings can give —

but stories done with guns and flags

are where we find we still must live.

The Book of his Addresses

The book of his addresses

is like the mind of God,

older than he’d like,

with some names down the bottom

seriously frayed.

Too many of its entries

have had a line drawn through —

and so he keeps on losing

the argument with death.

The entropy of God,

it’s clear, is heaven-sent.

Drawing near the silence,

the book of his addresses

becomes more eloquent.

The Smile

One thinks of those forgotten names

so smugly famous in their time,

masters of the parlour games

as well as of the tricks of rhyme.

They smile at their presumptive power,

Robert Santry, Stirton Giles,

heroes of the day and hour,

masters of the minor styles

that tell you, yes, that spring will bloom,

that God is in his highest heaven

that chancellors will bring no gloom

that dinner must be served at seven.

Such poets rarely die of poxes;

they are extravagantly mourned

then shouldered off in shining boxes

and given tombstones, much-adorned.

Oblivion now sets the pace

and ushers in the newer style.

Cheeks, in weeks, rot off the face

but nothing can destroy the smile.

Out There

The stars out there between the towns

reach right down to the edges —

or hang as if thrown up by chance

and casually tethered.

It’s ‘bible-black’ — except for them.

There won’t be any moon.

They’re floating there like funeral flowers

across a dark lagoon.

I have no wish to count them off

or be their registrar.

I’ve seen what’s out there way beyond

the city lights and cars

that flow like complex sentences

too difficult to parse.

I love the carbon compromise,

the smell of coffee bars.

from Korea

12.

Terminally naive, of course,

we’d thought to meet up later in

our swimmers and a swirl of bubbles;

instead of which we’re in our skin

with men and women separated,

sprawled in pools of varied heat.

We languidly compare ourselves —

and think about what not to eat.

14.

‘Why are Korean cars so big?’

I ask our young Korean friend.

‘Big man, big job, will need big car’

then tacks on slyly at the end:

‘Small man need a big car too

to show off to the other guys.

Our engines, though, quite often small;

we worry more with length than size.’

Reef

In all the glory of Linnaeus,

they’re swimming in their free verse world.

They’re like some catalogue of Whitman’s,

a triumph of the wide demotic:

the angelfish, the damselfish

and every sort of wrasse,

the surgeonfish, the triggerfish,

the flutemouths, snappers, fusiliers,

the cardinals, the goatfish,

the Bennet’s butterfly,

in widescreen and in technicolor

through every tremor of the spectrum;

the filefish and the parrotfish,

the clownfish with their whites and orange.

In all the reefs that still survive:

the pufferfish, the barracuda,

the jawfish on the bottom,

the anglerfish, the frogfish

in all their gothic splendour,

the seahorse, too, dealt straight from myth,

the hawkfish, gophies and the blennies,

the burrfish known as spiny puffer …

I saw them once, a small selection.

Unschooled in any Latin,

they swam beyond nomenclature,

rejoicing in their names.

Dancing by the Sea

Peace and Justice,

abstract nouns,

were meant to be together.

Transparent and

opaque by turn,

they love the salty weather.

How far back

does Justice go

and whose turn is it now?

The brawling boys

are in a queue —

the only question’s how

the local lad

will polish up

to ask her for a dance.

She’s delicate,

hard-pressed and rare;

he’ll have to take his chance

for both sharp sides

of Justice must

be honoured — then forgotten

as Peace, while waltzing

round the room,

wears only flimsy cotton.

And so our pair of

abstract nouns,

is dancing by the sea.

In bed together

afterwards

they dream of you and me.

2.

The sweat dries on

their bodies and

they’re languorously spent.

‘I shouldn’t tell you

but,’ she yawns,

‘you’ve lost the argument.

Waving guns

and gods and flags

can never be the answer.

No girl will ever

sleep with those,

however smooth the dancer.’

Young Justice doesn’t

quite know how

he got her into bed.

Who was it who

was following?

And who was it who led?

The boys back home

may spill their beer

and say he’s sold them out

but, now that he

has slept with Peace,

he knows what life’s about.

Their future may not

last the summer;

they have no guarantee.

A moon, though, pales

their bodies and

a breeze blows off the sea.

Quattrocento

It’s like a quattrocento painting,

the episode unknown,

some fragment from a vanished gospel.

A white-robed man is borne towards us

shoulder-high by seven more

dressed in what they wore that morning

expecting nothing worse than hunger.

The painter’s frame is dense with gesture,

one arm curved against the sky,

another raised in shock or protest.

Their faces are the timeless ones

old masters always use,

each one with its silent shout —

though one, we see, has tied

a sweatshirt round his nose and mouth

to clarify his breathing.

The colours are composed and careful —

blue shirt to the bottom right,

the sweatshirt’s high and sudden yellow,

that whiteness in the sky.

Top right there’s an edge of stone

ragged like some Roman ruin.

The man in white’s a deposition,

slanted from an unseen cross,

except he’s bald — and still alive.

The face is calm, and half-forgiving.

His feet are pale and bare.

The white he wears suggests the sacred

as does the crimson down his chest,

a vestment with some extra meaning,

until we see, at second glance,

the richness in that redness is

the sunlight in his blood.