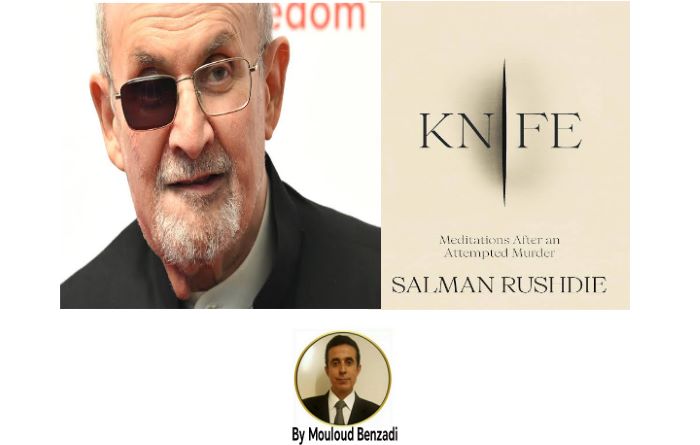

In his latest work, The Knife: Reflections on an Attempted Murder, celebrated British author Salman Rushdie takes an unconventional approach to the memoir genre. Rather than easing readers in with personal background or historical context, Rushdie plunges them directly into the harrowing reality of the knife attack he suffered. From the very first lines, he transports us to that fateful day: "At a quarter to eleven on August 12, 2022, on a sunny Friday morning in upstate New York, I was attacked and almost killed by a young man with a knife just after I came out on stage at the amphitheatre in Chautauqua to talk about the importance of keeping writers safe from harm."

Rushdie's Literary Journey Amidst Threats

The stabbing of Salman Rushdie serves as a grim reminder of the dangers faced by authors who challenge societal norms and provoke controversy. Rushdie's ordeal began in 1988 with the publication of his provocative novel, *The Satanic Verses*, which incited Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini to issue a fatwa for his death on February 14, 1989. Although the Iranian government retracted its support for the death sentence a decade later in 1998, the threat of violence from fundamentalists persisted, lurking even in seemingly safe environments. Rushdie was scheduled to engage in a discussion about the City of Asylum Pittsburgh project, which aims to provide refuge for writers in the U.S., yet this safe haven turned into a site of horror when he was brutally attacked at the Chautauqua Institution. Despite the constant threats that forced him into hiding and necessitated extreme caution in public appearances, Rushdie's literary spirit remained unbroken, leading him to publish works such as *Haroun and the Sea of Stories* (1990), *Imaginary Homelands* (1991), *East, West* (1994), and *The Last Sigh of the Moor* (1995), showcasing his resilience and commitment to his craft.

A Stalker Driven by Ideology

In Salman Rushdie's memoir, a thought-provoking question emerges: how much detail will he divulge about his attacker? The straightforward answer is not much at all. Despite the memoir format, Rushdie refrains from revealing the identity of his assailant, even after a 24-year-old New Jersey resident was arrested and charged. Instead, he opts for a series of references, labelling his attacker as “the A,” “my would-be killer,” “my assailant,” “my would-be assassin,” “a time traveller,” or “a murderous ghost from the past.” This choice not to name his assailant serves a significant purpose: it highlights the unimportance of the individual's name in a world rife with fundamentalists. The assailant could have been anyone among the millions of fanatic individuals and groups influenced by the old fatwa, emphasizing that the threat against free expression is not confined to a single person but is a pervasive and systemic issue.

The individual identified as Hadi Matar had watched Rushdie closely, spending nights in the vicinity and plotting his assault. Ironically, Matar's motivations stemmed not from a deep understanding of Rushdie's work, but rather from the infamous fatwa issued by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1989, as Rushdie highlights in his new book, “This ‘A.’ didn’t bother to inform himself about the man he had decided to kill. By his own admission, he read barely two pages of my writing and watched a couple of YouTube videos of me, and that was all he needed.”

Salman Rushdie’s Stance on Belief

In his novel “Knife,” Rushdie boldly expresses his stance on religion, leaving no room for doubt regarding his lack of belief in any form of religious faith or belief system. Rushdie makes it clear that he not only rejects organized religion but also dismisses the notion of anything that is unseen and lacks factual evidence, asserting, “I will express here, one last time, my view of religion—any religion, all religions—and then that, as far as I’m concerned, will be that. I don’t believe in the ‘evidence of things not seen.’”

Rushdie further emphasizes his stance on religious faith by stating, “I have never felt the need for religious faith to help me comprehend and deal with the world. However, I understand that for many people, religion provides a moral anchor and seems essential.” He expresses his respect for the privacy of personal beliefs, stating, “And in my view, the private faith of anyone is nobody’s business except that of the individual concerned.” He makes it clear that he has no issue with religion as long as it remains within the confines of personal belief and does not impose its values on others. However, he cautions against the politicization and weaponization of religion, noting its potential for harm. In such instances, he asserts, “then it’s everybody’s business because of its capacity for harm.”

A Balanced Perspective on Religious Extremism

In addition to the 1988 fatwa, another reason for Salman Rushdie’s negative image in the Arab and Muslim worlds is the belief that he is anti-Islamic, raising the question of whether he targets Islam specifically. The evidence suggests this is not the case. Rushdie has openly rejected all forms of religion, as he acknowledges in his recent book. His writings and essays consistently criticize various religions, not singling out any one in particular. For instance, in “Midnight’s Children” (1981), published nearly a decade before “The Satanic Verses,” Rushdie faced criticism for allegedly showing disrespect to Hindu deities by equating their spiritual love with the physical love of his fictional characters. Additionally, he was accused of desecrating Buddhism through the character Saleem, nicknamed Buddha, as a term for an old man. Rushdie’s critiques extend beyond Islam; he condemns the weaponization of Christianity in the United States, which has influenced the overturning of Roe v. Wade and ongoing conflicts over women’s reproductive rights. He also critiques the rise of radical Hinduism in India, leading to sectarian violence. Furthermore, Rushdie addresses the global weaponization of Islam, contributing to oppressive regimes like the Taliban and Iran’s ayatollahs, the knife attack on Naguib Mahfouz, and the suppression of free thought and women’s rights in many Islamic countries. Through his work, Rushdie appears to criticize the exploitation of religion rather than any single faith.

In conclusion, “The Knife” by Salman Rushdie stands as a powerful affirmation of the resilience of the human spirit in the face of oppression and violence. Through his unapologetic narrative, Rushdie underscores the precarious position of free thinkers in a world fraught with ideological extremism, reminding us that no space is immune to threats against intellectual freedom. The anonymity of his attacker serves to highlight the pervasive and indiscriminate nature of such violence, reinforcing the urgency of protecting voices that challenge the status quo. Ultimately, Rushdie's work is a rallying cry for the enduring strength of the written word, urging us to confront darkness with courage and creativity.