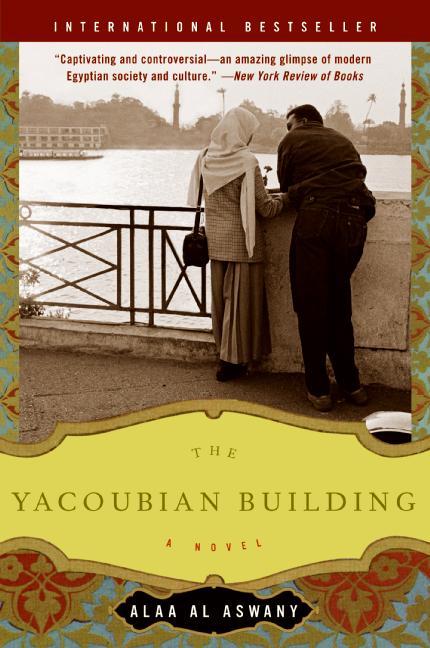

'Imarat Yacqoubian (The Yacquoubian Building), Alaa El-Aswani, Cairo: Miret, 2002. pp348

Reviewed by Mona el-Ghobashy Cairo Times 20-26 June 2002

A debut novel set in downtown Cairo during the 1990s brims with Mahfouzian characters and themes From the very first page, Alaa Al Aswani's Imarat Yacobian (The Yacobian Building) grabs you by the lapels and doesn't let go, drawing you into its world via sympathetic, finely drawn characters that could have been lifted straight from the canvas of daily life. There's the central Zaki Bey Al Dessouki, the francophone scion of a prominent Wafdist landowning politician who opts to stay in Egypt after the 1952 revolution and buries his professional failure as an engineer in heroin and women. The book opens with Zaki Bey's hour-long stroll from his house on Behler Passage to his office ten minutes away in the famed Yacobian building on Seliman Pasha Street, the literal and figurative centerpiece of the novel, built by a prominent Armenian millionaire in 1934 and bearing his surname. As Zaki leisurely makes his way down the street, in no hurry to get to the "office" he's turned into a love nest for his amorous couplings with women of all shapes and classes, he greets and chats with the shopkeepers and passersby, the traffic cops and shoeshine boys, telling dirty jokes with gusto and reminiscing about his bawdy youth. Then we're introduced to Taha Al Shazli, one of the best conceived characters in the novel, the God-fearing, hardworking son of the Yacobian building's bawwab who nurses a lifelong dream of becoming a police officer. He makes it through the tough written exams (all on his own, with none of the expensive private lessons lavished on his cohorts among the building's residents) and aces the oral but for one question posed by the examining officers: "What does your father do, son?" He's rejected, writes a letter of appeal to the president, is rejected again, applies to the prestigious economics and political science faculty, becomes alienated from the polarization of the student body into haves and have-nots, becomes an Islamist, gets imprisoned, is tortured and violated ten times with a thick stick by sadistic officers, and joins an armed group that conducts military training in the depths of the Tora desert. Al Aswani very deftly transitions from one character to the next, exposing us to the two worlds embodied in the Yacobian building: the haves who inhabit its spacious duplex apartments and the have-nots who create another society on its roof in the little storage rooms originally designed to house each apartment's excess foodstuffs and belongings. In the alternative, marginalized rooftop society lives Buthaina Al Sayed, a sweet, hazel-eyed girl who's Taha's sweetheart but becomes gradually estranged as the death of her father forces her to give up college and work to support her family; Hamed Hawwas, a self-appointed guardian of the "public space" that is the rooftop, endlessly reporting to the authorities some infraction or other committed by his neighbors; Abskharan, Zaki's aged, faithful office 'boy' who looks and lives like a bat; his conniving brother Malaak who maneuvers to illegally set up his tailor's shop in one of the rooftop compartments; Abd Rabo, a married Central Security Forces recruit from Upper Egypt who guiltily carries on a homosexual relationship with Hatem Rashid, the unpleasant but refined gay editor of the French magazine Le Caire; Soad Gaber, a poor Alexandrian widow who marries the lecherous old Hagg Azzam in secret to raise her only son from her beloved first husband, who died mysteriously in Iraq. Azzam is a millionaire drug dealer and MP who himself started out as a shoeshine boy and made it big, renting out an apartment in the building for Soad but requiring in the secret marriage contract that she not bear children lest his first wife find out. It isn't difficult to see how the Yacobian building is a stand-in for modern Egypt, with its rampant exploitation and inequality between rich and poor. Al Aswani is particularly concerned with sexual exploitation in its myriad manifestations, brilliantly driving home the point that the poor have not only been robbed of their dreams but of their very bodily integrity. Yet, sex and intimacy are also a balm and refuge from the daily indignities and cramped life conditions that the poor endure, and one of the most moving passages in the novel (reproduced on the back cover) sensitively speaks to this dimension. Al Aswani bathes all his characters with empathy and even affection, extended to even the most revolting among them. Take Kamal Al Fuli, a rotund, ruling party bigwig who commands veto power over who gets elected to the People's Assembly and demands LE1 million to get Azzam the Kasr Al Nil seat. Al Fuli is as vulgar as they come, talking with his hands, shoulders, and stomach like a market woman, but there's no doubt he has real political talent. "But this genuine talent, as happens to many talents in Egypt, became warped, deformed and associated with lies, hypocrisy, and intrigues so that when Egyptians hear the name Kamal Al Fuli, they think of corruption and hypocrisy," Al Aswani writes of his character. One of the highlights of the novel is when Al Fuli explains how the ruling party can't possibly be accused of rigging elections because Egyptians were born to be ruled and sheltered by a government and will always vote for the government, no matter what. "The Egyptian people are the easiest people in the world to rule over," he proclaims triumphantly. In its all-encompassing sense of place and the dissection of myriad characters' idiosyncrasies and aspirations, the novel bears more than a passing resemblance to Mahfouz's Midaq Alley. Buthaina is a broken 1990s version of Hamida, with none of the 1940s girl's soaring ambition. The well drawn characters, omniscient, matter-of-fact narrator (though with less descriptive elan than Mahfouz), the subtle handling of pathos and melodrama, the straightforward, non-preachy social realism, the humor'all serve as reminders of the novel's distinguished lineage. Al Aswani, a dentist with two published short story collections to his credit, has with this novel proven himself a master at forging complex characters and telling a highly readable, often moving story, no small achievement. But those looking for linguistic artistry or interesting formal structure will be disappointed. The language is thankfully highly readable and precise but not beautiful nor poetic. The transitions between characters are suspenseful in a soap opera kind of way. Possibly the recurring motif of the characters being likened to actors and acting serves as an interesting starting point for analysis, perhaps to underscore how life forces one to be a perpetual actor alienated from one's true self. Imarat Yacobian lingers with you long after you finish it. Its artful depiction of deferred dreams and broken spirits is sobering food for thought as the 50th anniversary of the July revolution approaches, and as Egyptians ask themselves how far we have really come when a bawwab's son can't become a police officer. Though the novel ends on a sweet, hopeful note, it is Buthaina's bitter testament to the fate of an entire generation that rings in your ears long after you close the book. "When you wait for two hours at the bus stop or have to take three rides and get hassled every day to return home; when your house collapses and the government leaves you and your kids in a tent on the street; when a police officer beats and curses you simply because you happen to be riding a microbus at night; when you spend the whole day going from store to store looking for work and not finding it; when you're all grown up and educated and have only a pound in your pocket and sometimes not even that; only then will you know why we hate Egypt."