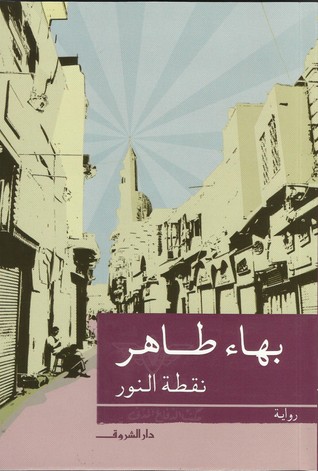

Book Review; Nuqtat Al-Nour (The Point of Light), Bahaa Taher, Cairo: Al-Hilal Novels, 2001. pp238

source Al-Ahram Weekly

By Youssef Rahkha

In Nuqtat Al-Nour, his latest work, novelist Bahaa Taher explores what for him is new territory, placing less emphasis on his usual concerns -- human beings and places -- and concentrating instead on "the spiritual thirst" of a brand new cast of characters.

While at first glance the novel's subject matter may seem familiar to admirers of the now-veteran novelist in its depiction of the fortunes of two Egyptian families during the 1970s, at a deeper level the novel is more concerned with what Taher understands by spiritual thirst, the hankering towards an extraphysical fulfilment or the lack thereof, demonstrating how this shows through and eventually breaks the novel's dramatic surface.

Dedicated to the renowned novelist and master of modern Arabic prose Yehyia Haqqi, Nuqtat Al-Nour actually deals with the mystical search professed by the old, quiet characters who populate Naguib Mahfouz's late novels, in which the predicament of death is confronted head on, professing a heightened knowledge of mortality and the quest for the meaning of life.

Divided into three, roughly equal parts, Nuqtat Al-Nour tells its story from the viewpoint of three closely related characters depicted mainly in the third-person: Salem, a lower middle class university student who lives with and is much influenced by his grandfather, a retired bashkateb (senior scribe in a government institution); Lubna, an upper middle class colleague of Salem's (their troubled love plays a central part in the unfolding of events); and the bashkateb, the patriarch of an extended family resident in a house built in the early 20th century in the middle class-turned-popular neighborhood of Sayeda Zeinab, Haqqi's locale. The choice of Sayeda Zeinab indeed comprises the most obvious link with Haqqi, whose memory the novel thus invokes.

The bashkateb's fight to rebuild the house following a derelict notification from the authorities, in the face of his son's ambition to pull down the edifice and replace it with a lucrative high-rise apartment block, provides the backdrop to Salem and Lubna's painful love, complicated by each of them being psychologically disturbed. Lubna, the only child of two successful physicians, now divorced, suffers a chronic existential fear. Combating this fear through engagement in the student movement, Lubna's brief arrest results in a nervous breakdown; and for a long while she is institutionalised in Rome. Salem, a Dostoevskian idiot, breaks down when their relationship is at the point of consummation. Eventually he too is institutionalised for treatment. It is the grandfather, however, whose Sufi search for love brings them back together while on his death bed. The novel ends with a Sufi insight: "Lubna asks Salem, 'Tell me, what did your grandfather say about spirits?' 'He said all spirits are beautiful and good.' 'But did he tell you what saves the spirit?' 'Yes, he said it was love.'