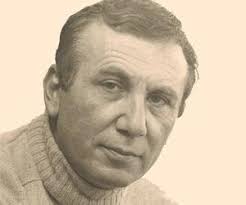

"The bird returns to its nest and the child to its mother's breast" -- words from Nizar Qabbani's last testament. Qabbani, who died at the age of 75 and was buried in his native Damascus, achieved unprecedented fame as an Arab poet, commanding a mass audience. The political stands struck in his later work fanned the flames of controversy to which Qabbani was never a stranger. Outspoken, never shying away from taboos, Qabbani nonetheless maintained a popularity that allowed him to abandon his career as a diplomat and concentrate full-time on his writing.

Before him, Arabic poetry was formal and grand. He inserted it into the language of everyday, modern life, thus making poetry a common property. His poetry accompanied kitchen utensils and became a fluid expression of the normal, the familiar and the simple in life, politics and sentiment. The reconciliation he effected was between poetry, on the one hand, and young students, housewives, clerks, professionals and heads of state, on the other.

He never paid attention to criticism. He broke away from the conventional and traditional structures of Arabic poetry without paying the least attention to what a modernist poet should aim to be or to related intellectual questions.

Qabbani was known and loved by those who do not read poetry -- even by those who do not read at all. There were elements other than love of poetry involved in knowing and loving Nizar Qabbani. One such element was the need to fantasise, to create an idol corresponding to fantasies that may have very little to do with the reality of the man idolised.

It was rebellious poetry which directly and bravely attacked all taboos. His extreme popularity lent him immunity from the suppressive arm of the authorities offended by his denunciations. Add to this the fact that popular stars like Mohamed Abdel-Wahab, Um Kulthum, Abdel-Halim Hafiz and Nagat El-Saghira competed to put music to and sing words written by him, and you get a glory never attained before by any other Arab poet.

He acquired a fame which even Ahmed Shawqi, dubbed Prince of Poets, was unable to attain and this despite the fact that people's evaluation of Qabbani's poetic ability varied while that of Ahmed Shawqi was unanimously recognised by his contemporaries.

Qabbani is a confusing poet. Most of his readers do not pause before the questions his poetry raises though there are some who do and insist on an answer. His poetry seems, more often than not, very simple. His vocabulary is not unusual, his syntax is mundane and his rhyme schemes are not complex. In short, there is nothing philosophical about his poetry. This lack of philosophising is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it gives his poetry an attractive spontaneity. This very spontaneity, however, dilutes its character since it becomes merely a reaction to, rather than an act of critical engagement with, life.

The simplicity of Qabbani's poetry does not mean that it is without value. It is true Qabbani can be read with great ease, but this does not mean that his poetry was written with the same degree of ease. He took great care to write in a way accessible to anyone and because of this his poetry will remain rich material for critics to analyse.

Each of us has his own Nizar Qabbani: discovering Qabbani is a part of the process of self-discovery during youth. Collections like "The Dark One Told Me" or "Childhood of a Breast" or "You are for Me" inserted us right into the heart of our youth. Without them we would not have realized that youth has a language proper to itself or that adolescent longing and anxiety have a place in writing.

Qabbani's works

Qalit li Al-Samraa (The Dark One Said to Me), 1944;

Tefoulat Nahd (Childhood of a Breast),

1948; Samba (Samba), 1949;

Inta li (You are for Me), 1950;

Qasaid (Poems), 1956;

Habibati (My Beloved), 1961,

Al-Rasm b'il Kalimat (Drawing with Words), 1966;

Hawamish ala Daftar Al-Naksa (Marginalia on the Notebook of the [1967] Disaster), 1967;

Yawmiyyat Imraa la Mubaliya (Diaries of an Indifferent Woman), 1968;

Qasaid Mutawahisha (Wild Poems), 1970;

Kitab Al-Hubb (The Book of Love), 1970;

Me'at Resalit Hubb (One Hundred Messages of Love), 1970;

Ashaar Khariga ala Al-Qanoun (Delinquent Poems), 1972;

Uhibik uhibik w'al Baqqia Taati (I love you, I love you, and the Rest Follows), 1978;

Kulu Aam wa anti Habibati (Every Year and You are my Beloved), 1978;

Ashhadu an la Imraa illa anti (I Bear Witness that there is no Woman but You), 1979;

Mawawil Dimishqiya illa Qamar Baghdad (Damascene Songs to the Moon of Baghdad), 1979;

Hakatha Aktubu Tarikh Al-Nissaa (Thus I Write the History of Women), 1981;

Qamoos Al-Asheqeen (The Dictionary of Lovers), 1981; Ashaar Majnouna (Mad Poems), 1983;

Al-Hub la Yaquf ala Al-Daw' Al-Ahmar (Love Does not Stop at the Red Light), 1983;

W'al Kalimat Taarifu Al-Ghadab (And Words Know Anger), 1983;

Qissati maa Al-Sh'ir (My Story with Poetry), 1983;

Qasaid Maghdoub alaiha (Scorned Poems), 1986;

Tazawajtik ayuha Al-Houreyya (I married you O Liberty), 1988;

Joumhouriyat Janounstan (The Republic of Crazyestan), 1988;

Al-Kabrit fi Yaddi wa Duwailatikum min Al-Warraq (The Match is in my Hands and your Little Nation is Made of Paper), 1989;

Al-Awraq Al-Sirriya li Ashiq Qurmuti (The Confidential Papers of a Lover), 1989;

La Ghalib illa Al-Hub (No Victor Except Love), 1990;

Hawamish alla Al-Hawamish (Marginalia around Marginalia), 1991;

Hal Tasmaeena Saheel Ahzani (Can You Hear the Neighing of my Sorrows), 1991;

Ana Rajul Wahid wa anti Qabila min Al-Nisaa (I am One Man and You are a Tribe of Women), 1993;

Khamsuna Aman fi Madih Al-Nisaa (Fifty Years in Praise of Women), 1994;

Tanweeat Nizariya fi Maqamat Al-Ishq (Nizarian Variations on Passion), 1996