source Al-Ahram Weekly- 15 - 21 June 2000

By Nadia Abou El-Magd

When I called Dr Nasr Hamed Abu Zeid, a professor of Islamic studies, requesting an interview, he said, "Why don't you come right away?" I was in Amsterdam. He was in Leiden, and we agreed to meet the following day in Leiden. Abu Zeid gave me a warm welcome. My actual presence in his home was, he explained, like "a part of Egypt coming to see me." Abu Zeid has not seen his homeland in the last five years.

On 14 June 1995, a Cairo Appeals Court for personal status litigation ruled that Abu Zeid, then a professor of Arabic literature at Cairo University, should be separated from his wife on the grounds that his writings included opinions that make him an apostate. The verdict was based on hisba, a doctrine that entitles any Muslim to take legal action against anyone or anything he considers to be harmful to Islam.

Abu Zeid's problems began when he applied for promotion to the post of professor. He submitted two examples of his research, Imam Al-Shafei and A Critique of Religious Discourse, to an examining committee. Abdel-Sabour Shahin, a professor of Arabic linguistics and a committee member, denied him the promotion and accused him of rejecting some fundamental tenets of Islam.

Abu Zeid appealed to the administrative court in 1993, but lost.

Then things went from bad to worse. His case became a cause c�lčbre after a group of Islamist lawyers filed a lawsuit at the end of 1993, demanding the breakup of Abu Zeid's marriage to Ibtihal Younes, a lecturer in French literature at Cairo University. The case was filed on the grounds that a Muslim woman cannot be married to an apostate.

Abu Zeid and his wife found themselves in the midst of national public scrutiny.

A Giza court threw out the case in January 1995, but it was accepted by the Cairo Appeals Court which ruled in favour of the plaintiffs. The marriage of Abu Zeid and Ibtihal Younes was declared null and void.

Ironically, the verdict came two weeks after Cairo University decided to promote Abu Zeid to full professor. For many militant Islamists, the court ruling was tantamount to a death sentence waiting for an executioner. Abu Zeid's life was under grave threat.

"After the verdict was handed down, I was accompanied by a police guard at every step," Abu Zeid said. "My last visit to Cairo University after that was to take part in debating a PhD dissertation in the Faculty of Arts, Islamic Studies branch. The university was turned into a military fortress to protect me. The question was, 'Will the university be able to take these measures every time I went there to teach?' It was impossible to teach like this and, at the same time, I could not imagine not teaching. On the way home, I told Ibtihal, 'This is not going to work out.' She nodded. If the professor is not able to teach, we might as well save the researcher. But a researcher can't function under guard either.

When some of our neighbours asked our guards why they were with us, they responded, 'because of the kafir [the infidel].'"

On the eve of 23 July 1995, the couple headed for Madrid, where Ibtihal was to attend a conference. On the plane, Abu Zeid told his wife, "I don't want to go back to Egypt, to the siege." They decided that they would go from Madrid to Leiden, where Abu Zeid had a standing offer to teach at its prestigious, 16th century university. "For the first time, we thanked God that we don't have children." Abu Zeid said wistfully.

I asked him directly, if he left Cairo because he was afraid for his life.

"I'm not afraid of death. What I'm afraid of is a disability that may result from an assassination attempt, like what happened to Naguib Mahfouz."

Noble laureate Naguib Mahfouz was stabbed in the neck by an Islamist militant in 1994. The stabbing left Mahfouz, incapable of using his handto write.

Ibtihal Younes has been to Egypt several times since the separation order, mainly to discuss MA and PhD theses at the French Department at Cairo University. Abu Zeid has not been to Egypt since 1995, despite invitations to attend seminars and conferences.

"Egypt, my country, has been taken away from me. I always took pride in playing a role, no matter how small it might be, in changing the way of thinking in my country through teaching. I have been denied this roleand thus I am denied the opportunity to repay all my beautiful nation has given me." Asked about his life in the Netherlands, Abu Zeid said that for the most part things were fine, "but I'm homesick. A friend of mine who is a psychologist told me that I'm not living in Holland, but inhabiting it. I still get lost in Leiden."

Abu Zeid filed a lawsuit last year against Justice Minister Farouk Seif El- Nasr, demanding an annulment of the separation verdict. On Monday, the Cairo Southern Court of First Instance decided to postpone the hearings until 31 July. In the interim, Abu Zeid will continue to teach at the Islamic Studies Department of Leiden University. He is currently lecturing undergraduates in Qur'anic studies and offers a course about freedom of opinion and expression in the Middle East. There are also a number of graduate students conducting Master's and Doctoral research under his supervision.

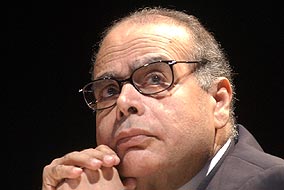

The past five years have changed Abu Zeid. Now bearded, Abu Zeid has lost 25 kilos since he left Egypt. His deep sadness is apparent in the tears that crept into his eyes more than once during the interview. His gaze, his voice and his endless desire to keep talking about how much he misses Egypt all testify to his discontent.

"I want to go and recite verses from the Qur'an at the grave of my father, my mother, and my sister. I want to visit the graves of my friends who have died during my exile: Shoukri Ayyad, Ghali Shoukri, Lutfi El-Kholi, Ali El-Ra'i and Fathi Ghanem." When asked what he doesn't miss about his homeland, Abu Zeid said, "I don't miss the fanatical atmosphere and the hypocrisy at some institutions. Some of the religious institutions are politically motivated. I oppose the intervention of religious institutions in the way we think."

As a victim of this "fanatical" atmosphere, it was important to find out what he thought of the latest controversy over A Banquet for Seaweed, a novel by Syrian writer Haydar Haydar. The book was denounced as blasphemous by Al-Azhar after the Islamist-oriented newspaper Al-Shaab spearheaded a campaign against it and against the Ministry of Culture for reprinting it. I asked Abu Zeid his opinion on the controversy.

It took Abu Zeid a while to respond. When he did respond, he said, "I'm following moment by moment the absurd discourse concerning Haydar's novel. It is absolute insanity." He continued, "Where is the crime here? Unless we live in the Middle Ages, I believe that the big crime here is everybody's wrongdoing: the government, the opposition, the Ministry of Culture and the People's Assembly."

Abu Zeid stressed the importance of a free and open dialogue between all social, political and intellectual forces. Constructive social dialogue is shut down once the accusation of "apostate" or "traitor" is raised. Abu Zeid explained to me that he was influenced as a child by the ideology of the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood. Though never committed ideologically, he was imprisoned at the age of 12, for allegedly sympathising with the group. "I was influenced by Sayed Qutb's ideas on social justice, I always identify with the oppressed," he said.

Abu Zeid rejects the accusation that he is anti-Islamic in any way. "I'm sure that I'm a Muslim. My worst fear is that people in Europe may consider and treat me as a critic of Islam. I'm not. I'm not a new Salman Rushdie, and don't want to be welcomed and treated as such. I'm a researcher. I'm critical of old and modern Islamic thought. I treat the Qur'an as a nass (text) given by God to the Prophet Mohamed. That text is put in a human language, which is the Arabic language. When I said so, I was accused of saying that the Prophet Mohamed wrote the Qur'an. This is not a crisis of thought, but a crisis of conscience."

Abu Zeid goes on, "I criticised the religious discourse and its social, political and economic manifestations, and this threatened the interests of some institutions."

He concluded, "I would like to tell the Muslim nation that I was born, raised and lived as a Muslim and, God willing, I will die as a Muslim."